There’s a recent paper on carbon cycle uncertainties and the Paris agreement (Holden et al. 2018). It considers two mitigation pathways, one that keeps end of century warming to below ~2oC, and the other that keeps end of century warming to below ~1.5oC. The interesting thing about the paper is that it uses a climate-carbon-cycle model (i.e., it considers emissions, rather than concentrations) and it also considers scenarios that don’t include negative emissions. The reason I wanted to highlight the paper is that it says something that I think is worth repeating.

A widely held misconception is that given the approximately 1 °C warming to date, and considering the committed warming (warming that will inevitably happen) concealed by ocean thermal inertia, the 1.5 °C target of the Paris Agreement is already impossible. However, it is cumulative emissions that define peak warming. When carbon emissions cease, terrestrial and marine sinks are projected to draw down atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2), approximately cancelling the lagging warming. Although the sign of this ‘zero emissions commitment’ is uncertain, its contribution can be neglected for low-CO2 scenarios. Therefore, at least when considering CO2 emissions in isolation, keeping below 1.5 °C of warming will remain physically achievable until the point that it is reached.

Essentially, it’s never actually impossible to keep warming below some level, until we’ve actually crossed that threshold. Of course, it’s not going to be possible – in reality – to immediately get emissions to zero, but I do think it’s worth recognising that our warming committment depends largely on how much we emit in future, and that the ocean thermal inertia does not mean that there is warming that we cannot avoid.

A couple of other interesting results in the paper. One was that the carbon cycle uncertainties contribute quite a lot to the peak warming uncertainty. The other is that in these rapid decarbonisation scenarios, decadal variability can dominate over the mean response in some critical regions. Something that I should probably make clear, though, is that even though it is never technically too late to avoid further warming, even this paper indicates that having a good chance of limiting warming to levels below about 2oC (relative to 1870) without negative emissions will require emitting no more – since 2017 – than about 300-400 gigatonnes of carbon. That’s about 30-40 years at current emissions. It might be possible, but it’s not going to be easy.

Update:

There is some criticism in the comments because I said “30-40 years at current emissions”. For clarity, I wasn’t suggesting that we simply carry on as we are for 30-40 years, and then instantaneously stop. I was simply trying to put the carbon budget into some kind of context. To limit warming to ~2oC is going to require (without negative emissions) that we emit from now (in total) no more than what we would emit were we to continue emitting at current levels for about 30-40 years. To do this will almost certainly require steep emission reductions starting very soon.

Links:

A bit more about committed warming (a post with some more details about our committed warming).

Emission reductions, negative emissions, and overshoots (a post about emission pathways that would satisfy the Paris goals).

It seems quite a stretch to claim that zero emissions could be instantaneously achieved at some convenient future point in time.

James,

Yes, I agree. Did I make it sound like that was possible, or are you referring to the paper?

our warming committment depends largely on how much we cumulatively emit in future,

It’s never redundant to specify “cumulatively”, since “how much we emit in the future” invites “how much we emit in, say, 2050”-so-what-ifism…

Agree with jamesannan – “That’s about 30-40 years at current emissions” hints at having 30-40 years. We don’t, unless we go from current emissions of approximately 11 GtC/year to zero virtually overnight. Which would be surely as difficult then as right now. We don’t have “30-40 years of current emissions” over those 30-40 years in any realistic scenario. They need to start falling – very sharply! – sometime well before the England-Croatia match.

rust,

Okay, fair enough, it is the total (cumulative) that we emit in future (I thought that was obvious, but maybe not).

Indeed, although I didn’t say “we have 30-40 years”, I was pointing out that the total we can emit, while still limiting warming to 2oC, is equivalent to 30-40 years at current emissions. This, to me, sounds like not very much and suggests we’d need to start reducing emissions soon (since we clearly can’t keep emitting at currently levels and then suddenly stop), but maybe others interpret this differently. So, yes, limiting warming to less than 2oC will require getting emissions to zero without emitting more than we would emit if we kept emitting at current levels for 30-40 years.

Well, back to jamesannan’s exact point:

Whether we instanteously go from 11 GtC to zero in 2018, or instantaneously from 11 GtC to zero in 2048 after “30 years of current emissions”, or instanteously from 5 GtC to zero in 2048 is both “quite a stretch” and quite important in terms of cumulative emissions.

The implication being that the emissions pathway has to be very, very steep in the interim as well.

I know you are informed on this, but my impression is that you sometimes lax on what the implications of the emissions pathways and budgets are. As I say, mostly an impression…

rust,

At no point did I claim that we would instantaneously go from 11GtC to zero. I’m well aware that getting from where we are now to zero emissions, while limiting warming to something like 2oC, will require an emission pathway that steeply goes from where we are now, to zero. What I’m less good at is remembering (especially when I write a post on a Sunday night) all the ways in which how I phrase things can be criticised. So, to be clear, I wasn’t suggesting that we keep emitting as we are for 30-40 years and then suddenly stop, I was simply trying to put the required carbon budget into some kind of context; we need to get to zero without emitting more than 30-40 years worth of current emissions. This is not going to be easy, as I said at the end of the post.

Maybe I should clarify something else. There is this tendency for some to claim that we have some amount of committed warming and hence there is little we can do to avoid some potentially significant amount of future warming. Technically, this is not correct, although the details do depend on various factors. Essentially, emission reductions can have an impact on decadal timescales and even if it’s not going to be possible in reality to get emissions to zero overnight, we shouldn’t assume that there is some amount of warming that the inertia in the climate system means we can’t avoid (the relevant inertia is societal/political).

I think some folks get confused about the difference between zero emissions and a halt to the increase in rate of emissions. The difference is quite significant. If we are adding 2 plus ppm of CO2 to the atmosphere every years and we need to get to 0 ppm increase, the path ahead requires a great deal of change in the way that our species functions on the planet. In the end, we need to stop talking about reducing emissions and talk about how we survive on a zero emission planet, or how many of us survive on such a planet or how we decide who gets to survive. Good post, thanks for your effort.

This is the idea we have to keep emissions within a certain carbon budget isn’t it?

I agree about the uncertainty that the study points out. But I guess some chance of achieving a target is better than no chance.

Looks like reducing emissions is the most viable path forward.

https://climatecrocks.com/2018/07/07/carbon-capture-and-storage-not-there-yet/

I listened to the presentation and the price of current carbon capture schemes are between $600 and $1,000 per ton of captured CO2.

Yes, if we could reduce emissions to zero, additional forcing would stop. However:

(a) Some physical processes, such as atmospheric response and especially oceanic response and ice sheets have build-in lags, and these will not stop.

(b) Reducing emissions to zero means somehow magically reducing agricultural emissions to zero, which are about 20% of global emissions at present. And, as I’ve noted before, these emissions have nothing to do with fossil fuel emissions in the service of agriculture or its transport or its processing, but agriculture itself, rice paddies, beef lots, soy beans, and the whole lot.

(c) At present, because there is no Carbon neutral replacement in hand, reducing emissions to zero would mean stopping all shipping and air transport.

Also, yes, there is a natural drawdown of CO2, but it’s at a time scale with which we are not used to dealing, about 2-3 centuries, and it won’t draw down all emissions, just an appreciable chunk. There are some which will remain for a thousand years and more. Also, it is important to remember (because I made this mistake once) that soils and oceans are in equilibrium with atmosphere so, if you capture and sequester CO2, by natural or other means, you also need to capture that fraction which went into oceans and soils. Essentially, what’s in atmosphere is only 40% of what we’ve emitted. Capturing means taking care of the other 60% too. It can be done, it’s just that the task, whether by natural or artificial means, is bigger and longer than if it was evaluated based solely on the atmospheric fraction.

But, yes, zero emissions is what any serious proposal for CO2 mitigation should have as its goal. CO2 is not CFCs, nor is it DDT.

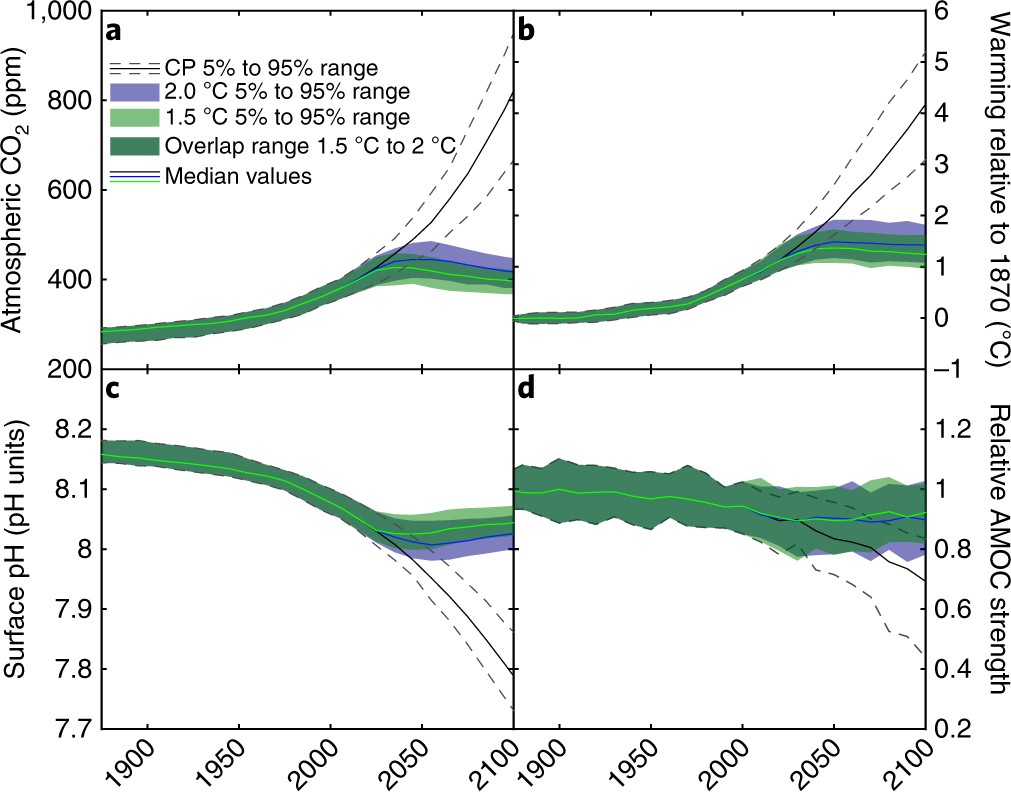

The paper low balls the aCO2 global observational time series starting in ~2010. They very conveniently did not publish the aCO2 time series as presented in Figure 1a (1P5 °C 5% to 95% range plus their central estimate time series). Their 2P0 aCO2 will depart (low ball) the observational time series (assuming a linear 2.4 ppmv/yr, which means that GHG emissions flat line starting in, oh say, 2013) in 2025.

Bottom line? Their “and then a miracle occurs” aCO2 time series must go linear then concave down in the 2019-2028 timeframe (e. g. the next decade).

Their conclusions are only valid if their low aCO2 plays out as depicted in Figure 1a, I’d put that probability somewhere between nil and nigh impossible.

Note to self: It would have also been kind of nice to see their assumed CO2 emissions time series.

Shell Oil, 1991:

It seems strange to be talking about zero emissions when a large part of society cares so little they will drive 300 yards to the shops to pick up 20 cigs and a Daily Mail.

Oh, here’s Figure 1 …

(X-axis starts in 1875, not too sure their temperature time series matches very well the GMST records, why no model/observational comparison, one wonders. Also it is reasonably well known that aCO2 pretty much flat lined in the 1940’s.)

Click to access bg-13-4877-2016.pdf

@AndyM,

Setting aside the health benefits of not doing exactly what you describe, clearly, the answer is substituting a mode of transport for that 300 yards which emits nothing, and making that choice so financially compelling it is self-evidently stupid not to use it. It’s on its way, the long range EV and a zero Carbon way to charge it. The attractive plum is both its low energy and maintenance costs.

This kind of technological innovation under people’s noses despite their inclinations is why I think the answer here is enlightened technological innovation. It could use some central coordination, however, and I very much appreciate that coordination need not come from government.

Note, however, if it doesn’t or if it is not enlightened, government is setting itself up to be disrupted by other coordinating and facilitating social structures.

There is no misconception that further warming will occur at least for some time. The possible misconception may be that the further warming will last for a long time. The benefit of immediately ceasing emissions is that it hopefully won’t be long until global warming gets back down to its value at the point in time that emissions ceased. Further warming will occur after emissions suddenly cease completely, but this further warming will hopefully be reversed before long.

I missed a discussion of non-CO2 forcing that is associated with fossil fuels, eg. aerosols that cool, but there are also others that warm. If you would choose to immediately stop emitting, the net effect of removing these short lives species is to warm the planet. In not sure if the paper handles this, and it may be hardly noticeable in this type of scenario, but it breaks apart the idea that temperatures stay constant after you stop emitting.

Thorsten,

Indeed, good point. I linked to my post about your paper in one of the comments, but I’ll add a link at the end of the post.

Chris,

I don’t quite agree. I regularly see people claim that the inertia in the climate system means that there’s substantial warming (~0.5C) that we simply can’t avoid.

@ATTP, @Chris O’Neill,

The latest major go-round I’m aware of on this is the massive response to 2016’s Snyder paper, namely,

G. Schmidt, et al, “Overestimate of committed warming”, Nature, 547, E16-E17 (13 July 2017)

There is some additional committed warming from the release of methane from methyl clathrates and from permafrost. A minor amount of the latter can already be observed in a few locations in Siberia. Neither source may amount to much but this is a positive feedback.

David,

Yes, but I think that for scenarios in which we decarbonise rapidly, and limit warming to below 2C, that effect is expected to be small.

“Chris,

I don’t quite agree. I regularly see people claim that the inertia in the climate system means that there’s substantial warming (~0.5C) that we simply can’t avoid.”

I certainly thought that was the case, wrong? If so it would make me re evaluate allocations of funds to adaptation. My sense was we would see this commitment regardless, so we should at least to start adaptation to the warming in the pipeline

Steven,

I guess there are two issues. Even if we can technically avoid any future warming, actually doing so would require halting all emissions now, which is never going to happen. There are clearly going to be further emissions, so some amount of warming committment is probably unavoidable. Another factor is that avoiding future warming requires getting emissions very close to zero. Even a ~90% reduction in emissions over the next few decades would mean that atmospheric CO2 would continue to accumulate (or wouldn’t drop). See the second set of figures in this Steve Easterbrook post.

The inertia we really need to be concerned about is in infrastructure and the structure of economies.

We are currently investing hell for leather in inherently high carbon infrastructure such as low spec housing, new airport runways and unconventional hydrocarbon extraction.

These investments will continue to drive CO2 emissions for decades to come.

Steven,

I think it would be wise to continue spending on adaptation as we have a poor understanding of our baseline climate and an even poorer understanding of what climate change impacts are to date. This is mainly due to our understanding (or lack of) of internal variability due to length of datasets, particularly for hydrological related impacts such as floods and droughts.

My wife has just had her Nature CC paper accepted which shows, from observed data, a larger increase in extreme sub-daily rainfall than previous observed or expected from theory.

andy says: “It seems strange to be talking about zero emissions when a large part of society cares so little they will drive 300 yards to the shops to pick up 20 cigs and a Daily Mail.”

We need to change the narrative more abruptly than we reduce CO2 emissions. The strange thing needs to be clearly identifies as driving 300 yards for 20 cigs and a Daily Mail.

Also, I don’t know if the Daily Mail is worth the trip in any case.

”

Also, I don’t know if the Daily Mail is worth the trip in any case.

”

That depends entirely on your sense of humour.

> The inertia we really need to be concerned about is in infrastructure and the structure of economies.

I’d add cognitive structures:

https://twitter.com/nevaudit/status/1016333450876506112

Indeed.

Daily Mail front page generator

http://coyoteproductions.co.uk/silly/dmhg/

This was the front-page pic for my second hit. Headline: “ARE HOODIES CHEATING HOUSE PRICES ?”

And there’s even a Daily Mail story generator!

“A widely held misconception is that given the approximately 1 °C warming to date, and considering the committed warming (warming that will inevitably happen) concealed by ocean thermal inertia, the 1.5 °C target of the Paris Agreement is already impossible.”

The above is an informal logical fallacy, called a strawman, hmm err, strawperson.

“Therefore, at least when considering CO2 emissions in isolation, keeping below 1.5 °C of warming will remain physically achievable until the point that it is reached.”

Is that a true statement if we bust right through 1.5C at 3C/century or 2C/century (roughly current rate) or even 1C per century? I think not.

Hope springs eternal in the human breast;

Man never is, but always to be blessed:

The soul, uneasy and confined from home,

Rests and expatiates in a life to come.

RCP 2.6 from IPCC AR5 WG1 Chapter 12 Figures 44/46 …

I’m going with the RCP 2.6 blockhead profile. Because I would just have to be a blockhead to believe this paper. Assume we are (and will stay) on an RCP 2.6 pathway starting in 2010!

Star light, star bright,

The first star I see tonight;

I wish I may, I wish I might,

Have the wish I wish tonight.

Sorry for being such a Negative Nancy/Debbie Downer but I like to use the IPCC uncertainty language (p. 36) …

Click to access WG1AR5_TS_FINAL.pdf

It is exceptionally unlikely that we will stay at or below RCP 2.6 over the next 32 years (2050). It is virtually certain that we will remain at, above or close to, RCP 4.5 over the next 32 years (2050).

@Everett F Sargent,

Excellent post @July 9, 2018 at 4:58 pm, Everett.

@-andy

“It seems strange to be talking about zero emissions when a large part of society cares so little they will drive 300 yards to the shops to pick up 20 cigs and a Daily Mail.”

At least they don’t give them a plastic bag to put it in anymore…

I expect Dave_G might know more, but economic reports indicate that the fossil fuel extraction and energy industries expect the same level of production to continue for several more decades, or increase.

None are warning their shareholders that they have stranded assets that cannot be burnt in exchange for money in 20 years time.

I am wary of dismissing the possibility of a very rapid decarbonisation of the World economy a few decades ahead.

If you buy into the ‘Seneca cliff’ hypothesis of rapid collapse then four horsemen, spurred by climate impacts could eradicate the global economy in a decade.

If some nations or the system is slightly more resilient, it may leave a 10% still causing ~10% of present emission.

Or a unicorn appears and emissions are reduced at 1%/year until the residual level is 5%-10% by 2100.

What is the temperature trajectory under those ‘RCPs’ ?

izen said “I am wary of dismissing the possibility of a very rapid decarbonisation of the World economy a few decades ahead.

If you buy into the ‘Seneca cliff’ hypothesis of rapid collapse then four horsemen, spurred by climate impacts could eradicate the global economy in a decade.”

I think that is exactly right. I think when we talk about the need to get to zero emissions (or closer thereto) we need to mention the ways that this path might be forced on us without any mitigation or management of human suffering. More people need to understand that when we talk about something being unsustainable, it means it will stop at some point. We have input and choices to make about how to modify unsustainable practices, but if we do nothing it is almost certain that we will have a needlessly painful end to unsustainable practices. I think my kids and grandkids may live to see us experience the default option to global warming.

According to Zeke Hausfather’s pinned tweet (which was published last November), the pathways to 2C warming assuming no negative carbon solution are currently already practically impossible and get worse with each passing year in which emissions are not decreasing.

So, speaking purely on a rhetorical level, I don’t think that saying “That’s about 30-40 years at current emissions” is either terribly accurate or helpful. Per Zeke’s graph, we have zero years of current emissions, followed by ever more difficult efforts to reduce emissions with each passing year, in order to max out at 2C.

Francis,

I’m not sure how many times I need to clarify this. “30-40 years at current emissions” was intended to illustrate the total amount we can emit. Given that we’re emitting about 10GtC per year, this is 300-400 GtC in total. I think this is broadly consistent with Zeke’s numbers. In order to not emit more than this (in total) we would indeed need to start reducing emissions soon and follow a steeply falling emission trajectory. I wasn’t suggesting that we can keep emitting at current levels for 30-40 years (in fact, here is a Carbon Brief article, the first figure of which presents it in the same way I have – 27.8 years at current emissions to have a 50% chance of keeping warming below 2oC).

@izen, regarding stranded assets and investments, per

That’s pretty broad. In fact, I’d say it’s incorrect. Sure, a number of the majors are denying that stranded assets are a problem. But they don’t control that determination, even if they might influence it. Increasingly, analysts, auditors, their (financial) insurance companies, and regulators are examining these risks ever more publicly, and whether or not they own up to the problem, it’s going to become one whether they like it or not.

Thomson-Reuters cares about this. The Financial Stability Board has a task force on standard disclosures of climate risk.

The Economist has covered much of the discussion.

Also, investors oughtn’t think that energy companies are the only ones with appreciable exposure to climate risk, even to stranded assets. There are appreciable risks in recreation and of course insurance as well.

@izen,

Sorry for the choppy multipart responses. I didn’t see this

until later.

There’s a more pressing risk which Mark Carney, BoE Governor often highlights. Stocks are in a marketplace. There are other assets, such as real estate, which also depend upon a market for price stability and support. Carney speaks about his fear of a Minsky moment when risks which investors had underestimated or underpriced become real enough cause substantial sales and deleveraging of associated debt. Not all or even most investors need to do this. It can suffice that key ones or leaders do, and, then, whether others make the same determination or not, they are afraid of getting caught in a panic, sell, and, so, precipitate one.

The point of this is the Minsky moment can come whether or not there are actual climate losses. One in real estate could come if the risk posture of the federal government changes because they can’t carry the risks any long on their books, and people no longer have a safety net. It can happen as a result of litigation. And, of course, it can happen because of competition.

@Francis,

Stocker’s famous closing door …

attp, yeah I was agreeing with you, I think. I haven’t actually read the paper, only your paraphrasing of it, but assuming they are talking about some sort of BAU followed by an instantaneous drop to zero, I wonder about the relevance of such a scenario. Nice to bump into (be bumped into by) you the other day BTW!

James,

Ahh, maybe I’ve paraphrased it badly. I actually can’t find a good description of their emission pathways. They used two, one that limited total emissions to 200GtC and the other to 307GtC, both post 2017. These kept warming below 1.5C and below 2C (reaching 1.7C in 2100). I don’t think this was done by simply halting all emissions after some number of years. They do have a whole section describing their scenarios, so they do seem to be trying to justify how such pathways could be followed (although they don’t seem to show the actual pathways). I was mainly just commenting on how difficult this would be even if we tried to reduce emissions more gradually than simply suddenly halting them at some time.

Good to meet you too. Apologies if it was a bit startling. I shall have to work on how to introduce myself to people I only know on social media, especially if I’ve also just ridden 7 miles in temperatures rarely seen in Scotland 🙂

I think I may have spotted you and your partner receiving triathlon awards a few days ago too. Very impressive time, but I think your fancy dress may need a little work…

Okay, I think I see where the issue is. I said:

I was really just commeting that even though it is never actually impossible to keep warming below some level until you actually cross the threshold, if we don’t start reducing emissions with the aim of getting to ~zero, then there will come a point where avoiding crossing this threshold would require a complete cessation of all emissions which (if we are still emitting many GtC) would be unrealistic.

Re share prices and stranded assets. In two parts.

Well, you could look at BP’s energy outlook report, which I believe has some credence in the industry. It posits three scenarios for decarbonisation, none of which features a hard stop. It’s presented as a public service/noblesse oblige thing rather than as a guide to investors, and for the industry/globe not BP specifically. Otherwise it would get tangled up with lawyers and SEC bureaucracy. They’ve been doing it for decades so it has the merit of year-on-year consistency. Not sure why they do it. Maybe it was instructed to do so back when it was state-owned and just carried on.

In principle, investors should look at companies’ SEC Reserves, which is what they’re there for. Certainly asset swaps and sales/purchases take great account of them, particularly proven reserves as I know having been involved in many from both ends. Which is interesting as they’re actually a pretty poor indicator of asset value. Anything that make a cent a barrel profit at year-end (not even averaged over the course of the year, which they used to allow) is in. Anything that doesn’t is out, even if it made $10 a barrel the rest of the year but was hit by a short-term price fall or cost spike. Like some US safety rules, it seems to be designed to make it simple to identify and prosecute cheats, than to truly inform investors.

Professional investors are not so stupid as to base their decisions solely on what the company says, especially as it usually comes with “forward-looking” boiler-plate which translates to “don’t hold us to this with the SEC”. That’s why they have analysts. I think they’ll have read the IPCC reports and the Paris Agreement, don’t you? That’s what they’re paid to do. A moderate decarbonisation programme will be priced in already.

Proved reserves need to have been flow-tested and to have development funds sanctioned, and even then each reservoir unit has to flow commercial production before it gets into the top category. Arm-waving resources which are not close to development are icing on the cake and don’t really get priced in. For example, an old rule of thumb used to be $1/bbl for proved reserves, 10c/bbl for unproven resources and 1c/bbl for exploration prospects (and that’s applied to oil-in-place x recovery factor x chance of success – the number you’ll read in the newspapers is oil-in-place or if they’re more technical, oil-in-place x recovery factor). Unless a small company makes a big discovery and is predicting resources an order of magnitude bigger than their reserves, it’s all about the reserves. Did Shell’s share price fall when it pulled out of the Arctic? And did it fall more than you’d expect just from the billion-dollar write-down? Probably not. It may even have gone up, as investors like management to show steel and not throw good money after bad.

So in practice, it’s only a three to four decade lookahead, with the later decades discounted. And most fields only have a 5-10 year production plateau then decline, so production as well as revenue is discounted. And the per-barrel cost of production tends to go up later in field life. So most of the NPV is in the first decade. For workovers (well interventions like refracs), many companies screen on the basis of an 18-month payback. US fracced wells are like that from the word go. Investors look at reserves replacement rate to value the long-term, not banks of unproven resources. To decarbonise, the industry just has to stop investing and natural decline will do the rest. Often that yields the highest NPV, so short-term activist investors may well pile in and push the share price up. My first employer seriously considered stopping all investment and monetising its assets in 1986. Only a fall in the cost of services and supplies, which made some investments profitable again, stopped them

So no, investor lawsuits alleging that the companies lied about their prospects 50 years ahead won’t fly. Or, at least in the US, they’ll only fly as high as the Supreme Court before being over-ruled. Especially now that everyone says they believe the IPCC. As everyone bar ExxonMobil and Chevron have been saying since the 1990s. The courts won’t reward blind or stupid investors, especially when it’s well known that most O&G investors are in it for the dividend, not for share price growth. It’s the complete opposite of Silicon Valley. Unless you can demonstrate actual fraud, e.g secretly funding a denial campaign. Most of that AFAICS comes from rich investors like the Kochs (who are their own shareholders – will they sue themselves?) or politically-motivated “thinktanks”, not SEC-quoted O&G companies.

For perspective on why some shareholders might find active decarbonisation by O&G companies attractive: Shell’s capital investment last year was double it’s total dividend payout. In 2015 it was more than five times bigger (that included the BG purchase). And that’s a company that’s under a cloud following a series of management missteps, at a time of low oil prices. Which payed 4.37% dividend, although it had to dip into reserves to do so. Under more average conditions, you could probably sustain a dividend yield of around 10%, albeit against a declining asset value. Would I take a 10% rate of return on an asset, even one I knew would have zero value in 30 years time (and concomitant with that, the dividend also declines to zero in thirty years time). Absolutely! It’s a no-brainer compared with putting the money in a bank and getting 1% interest if I’m lucky.

Back on topic, there are a few things to remember about the concept of stabilising temperature by going cold-turkey, or even doing the same with an emissions trajectory that declines to zero.

Non-substitutable emissions like agriculture have been mentioned. So there is some merit in a path which allows us a small long-term emissions budget, to be offset ultimately by negative emissions (but allowing, say, a century for them to develop). Baked-in SLR, steric as freshly warmed surface waters continue to mix down at constant surface temperature, and ice-melt. Ocean acidification will continue, as it’s ocean CO2 absorption which counteracts the in-the-pipeline warming. So it needs to be made very clear that a temperature fix wont fix them. Otherwise the public will feel cheated.

Also long-term, we need to consider Earth System feedbacks like albedo change from disappearing ice caps. If we’re lucky that will take a thousand years, but do you feel lucky? Regardless, a centuries-ahead GCM projection will underestimate long-term temperature rise. At least with ice, we’ll see it coming. Maybe not with methane burps. Both are essentially unstoppable. Due to hysteresis, icecap loss is irreversible until we get down to much lower temperatures, probably below pre-industrial.

In one sense arguments about precisely how much bigger ESS is than ECS (e.g. Schmidt/Snyder 2017) are immaterial. As I understand that argument, it’s that the tipping points which tipped in glacial-interglacial cycles to give such a large ESS, won’t tip today because we’re in the wrong part of the Milankovitch cycle. But the Milankovitch trigger was so small we can’t model it convincingly. So presumably some other very small perturbation could trigger the albedo tipping point. Such as demolishing all those Chinese houses with CFC-bearing wall insulation some time next century.

The more important thing is how fast we transition from the ECS to the ESS timescales. The Schmidt ESS in 500 years would be a lot worse than the Snyder ESS in 5,000 years. Recognising ESS is another reason to consider (but not bank on) pathways incorporating negative emissions. If we want to stay at a fixed temperature, we’ll need them eventually. And if we cross a tipping point, we’ll need them in a hurry. Better to start now, with subsidised baby steps, than to have to develop the technology from scratch under severe time pressure.

@Dave_Geologist,

Regarding investor, city, and state lawsuits against fossil fuel companies, while I think there may be merit to these in order to establish producer primary responsibility for product in order to counter the consumer made me do it arguments, anyone who thinks imposing large penalties on the companies and then using that to help solve the decarbonization transition or clean up atmospheric CO2 has not done the numbers. The entire assets of the world’s fossil fuel industry, even if it could be liquidated perfectly intact, are massively insufficient to do either of these things.

If people don’t like fossil fuel companies, don’t invest in them. (I don’t, except possibly indirectly by owning shares in the high yield bond fund, VWEHX.) There are plenty of alternatives, including the SPYX ETF, which shadows the SPY (S&P 500), ex fossil fuels. But, nevertheless, the only sensible thing is to hope that they can be turned around and their talent and engineering skills marshalled to the task of making the transition and especially to the clear air Carbon capture problem. As @Dave_Geologist has admirably demonstrated, the sequestration bit of that could really use their help.

That said, and Schumpeterian as I am, I emphasize hope because, historically in business, entrenched, successful companies have a pretty weak track record of realizing that their main business line is doomed, and converting. Usually outsiders take up the job.

It would be refreshing to see some ex-oil and ex-coal people branching out and taking this on, independent of their original careers. From what I understand T Boone Pickens wanted to go big into wind, as others in Texas have, but was frustrated by utilities’ preference for natural gas. The latter is what the Schumpeter in me would expect.

And then there’s astrophysics:

Well, after designing and building his own electric guitar

in his schooldays, which has served him for 50 years, refurbishing a spectrometer would have been a piece of cake 🙂 .

Some good quotes:

Well, there are times in a concert where you just have to smash your guitar. Like with rackets at Wimbledon 🙂 .

Turn it up to 11! (h/t Spinal Tap).

And of course the knife-edge tremolo was made from an actual knife.

hyper, I both agree and disagree with “producer primary responsibility for product in order to counter the consumer made me do it”. The difference is that I identify the product as CO2, not oil or gas. ExxonMobil is only the primary producer of the CO2 it releases in its operations (and fugitive CH4, and any residual CFCs released when they decommission a refrigeration train or a fire-suppression system). When you burn that stuff in your gas-tank, the stuff that goes out the back is your CO2, not ExxonMobil’s.

There is also a practical consideration, Apart from stateco’s like Statoil and Aramco, O&G companies don’t own any oil or gas reserves. Landowners (in a few countries) and governments (in most of the world) own the oil and gas, and continue to own it even after fields go into production. The O&G co’s negotiate a licence to extract and sell the product, in return for paying tax and royalty to the owner (defined loosely here so as not to exclude OPEC PSAs/PSCs – tax is payment in cash to the owner, up front or during production, royalty is payment in kind). If XoM turned round and said it would shut in field X voluntarily because of climate change, government Y would say “that’s a breach of your licence terms, we’ll award the production licence to someone else”. That’s why it needs government action.

The two big-bad-oil-company myths which get in the way of real action rather than fantasy action are:

1) That there’s enough spare cash sloshing around in O&G company profits to convert to a low-emissions economy with no cost to or sacrifice by anyone else. There isn’t. By orders of magnitude. Their working capital comes ultimately from investors, not some magic money-tree. With the right tax incentives, they’ll build wind farms. But only as a profitable investment. BP has built loads in the USA. And was once the world’s biggest solar manufacturer, but got out when it started losing money because Chinese product was cheaper. And has just bought a UK rapid-charging company to roll its product out to all BP gas stations. As Shell did last year in The Netherlands. [I know you appreciate this one already so it’s for a general audience].

2) That we’re not to blame, only oil companies are to blame and if they would just cut back production, we’ll all magically stop emitting. We won’t.

P.S. I have worked on a CCS project. It fell through due to government dithering.

@Dave_Geologist,

So on this, I completely disagree. The product is oil and gas. It’s just that if you use it in the way it’s intended to be used, it destroys the climate. It’s like selling oil for things contaminated with Dioxin, or products that are intended to make a lawn greener which cause cancer, or a drug which is intended to control high pressure which, in 0.5% of the population, destroys kidney function. (That actually was a drug that passed FDA muster.)

Accordingly, the origins of the Carbon in reservoirs or whatever don’t matter. It’s product liability problem.

We’ll have to agree or disagree hyper. There’s a difference between a product which intentionally or unintentionally causes harm, unknown to the consumer, and a product where the consumer knows (or ought to have known) about the harm for decades. Where even the producers have said since the 1990s that they accept the IPCC findings, which include of course climate-change induced riaks and hazards. Caveat emptor. The buyer alone is responsible for checking the quality and suitability of goods. CO2 is a known hazard and has been for decades. The buyers have no excuse for consuming products that emit it. Indeed, here in the UK buyers are ‘trading up’ to SUVs from hatches, knowing fuel consumption is higher, to the extent that it’s cancelled out the emissions benefits from improved engine efficiency. Aware buyers are going right on emitting. And one of our largest public transport operators is in financial trouble, because more people are travelling by car despite no real wage increase since 2008.

I think under law, product safety is a strict liability question. It’s not like negligence where malfeasance, misfeasance and nonfeasance come into play, it’s just simple: if you make a product that is inherently unsafe, you may be held accountable for injury that follows production.

These are interesting arguments about liability, but I think it may actually be the case that both producer and consumer of these unsafe products should shoulder a portion of the blame at this late date, but the strict liability of an inherently unsafe commercial product appears to put more on the producer imo. I am not an attorney, I ran a freelance paralegal business supporting attorneys. My thoughts are not legal advice, paralegals can’t provide legal advice. These are merely my opinions based on a tiny amount of special knowledge.

Since the end game of the unsafe product is the sixth great extinction, it is difficult to figure damages and how they might be apportioned and whether the question itself has meaning in the real world. Standing for damages is reserved to the living generally, extinction and death would probably extinguish standing to bring the action or collect damages.

Zero emissions still seems like a good idea, however we might get there.

Mike

Mike:

Sounds like a zero sum game. If everybody is liable for damages, is there really any point in trying to collect and distribute damages? The cost in energy in computing the damages, collecting and distributing might actually emit more CO2 than if we just ignore the damages.

Thoughts on how to allocate:

Measure the amount of CO2 each person exhales over the life of each person, pick a damage amount, allocate accordingly and collect yearly.

Measure the distance driven using an ICE over their life, pick a damage amount, allocate accordingly and collect yearly.

Measure the amount of smoke emitted from cooking fires over the life of each person, pick a damage amount, allocate accordingly and collect yearly.

. . .

As you can see – this process, in and of itself, would emit a lot of CO2 and is rather pointless.

Plus, I object to being taxed for breathing.

Maybe it would be cheaper and use less energy to just gradually switch to producing all our electricity with nuclear power.

@Richard Arrett,

This is funny. Actually, one of the counters to overpopulation concerns is that humans are large animals and, similar to but somewhat less than forests, sequester a lot of Carbon in their bodies for 70 years. Moreover, apart from fossil fuel fertilized plants and animals, it’s Carbon that’s come from atmosphere and oceans.

(1) Cremation is probably a bad idea. Slow microbial “burning” is more efficient and better than rapid, which generally needs a fossil fuel booster.

(2) There’s no mystery at all in how to do the risk allocation: Just withdraw all government price support s for damages, protecting life and limb only, and don’t bail out companies, as President Obama and company did for GM and others. It’ll work out.

(3) In trade, pull all incentives for solar and wind. And any special favors for fossil fuels, including the Natural Gas Act, and the eminent domain it entails. I know who will win.

I’ve contradicted my case for government intervention earlier, but that’s not at a scale that is working.

The problem with that argument is that oil and gas are inherently unsafe in the same way that water is inherently unsafe. I.e. not. There’s a dose-response curve and we’re exceeding the safe long-term dosage.

If it was that simple, why has no-one thought about it previously? Oh wait a minute. They did. And lost. In California. If you can’t persuade a California court, good luck persuading a Supreme Court which will have a conservative majority for generations.

And you’re right, there is also the question of standing. In the unlikely event of getting it to fly, you’d probably be restricted to actual damages suffered by living people.

Richard, see my above, dose-response curve. The amount of CO2 emitted by us breathing falls well below the unsafe threshold. So relax, no breath tax. Although, hyper, I’m pretty sure we’re less efficient at carbon sequestration than trees. Tress don’t walk around, play sports etc.

And yes, there is the “where do you allocate blame”. Although courts already have experience in that area. For example, damages are routinely reduced where the victim was x% to blame. So someone then has to decide how much blame to allocate to Chevron for selling the gasoline, and how much to the consumer for buying a 4WD truck that never leaves the city, where a Prius would have served just as well. And on the present-damages-to-living-people premise, how much flood damage do you allocate to a power company or coal miner, how much to the government for subsidising insurance in increasingly flood-prone areas (even governments which accept the IPCC science and know flooding will get worse), and how much to the homeowner for not recognising their location is untenable and upping sticks? And do homeowners who accept the science get 100% damages, but AGW deniers only 50% because their denial contribution to their decision to stay put?

Nah, let’s not go there, lets change regulation/taxation/policies instead.

@Dave_Geologist,

Not to put too fine a point on it (with apologies to Dickens), forest Carbon dynamics are complicated, particularly if the forests are repeatedly disrupted, whatever the source. Obviously, wildfires can make a dent, too.

There’s an entire literature on this, and the sequestration isn’t only or even primarily in wood, but also in soils and root systems. A key paper is

S. Luyssaert, E.-D. Schulze, A. Börner, A. Knohl, D. Hessenmöller, B. E. Law, P. Ciais, J. Grace, “Old-growth forests as global carbon sinks”, Nature, Letters, 455, 11 September 2008, doi:10.1038/nature07276.

What’s intriguing is that young growth forests can be carbon source. Accordingly, there is something to the argument that, for instance, clear-cutting young forest to establish a large solar farm is a win if the forest has recently regrown from previously cleared farmland. The threshold for young vs old is 200 years. As always, YMMV.

quite right, DG. Let’s not go there – apportioning blame, let’s expend the effort on getting things right as soon as possible. The legal system is well-developed and has lots of experience at assessing causation of damages and apportioning blame, but that system is embedded in a complete socio-political-economic system that may be insufficiently capable of responding to the crisis of AGW. Time will tell on that.

For now, the time,money and diminishing resource wasted on struggle and fights within a system may be incapable of responding to AGW is simply that: a waste.

Our situation with a damaged ecosystem and diminishing resources may play out to near-universal impoverishment over time by many means. One of those means would be money wasted in legal battles. Another would be loss of value in stocks and bonds, the meat and potatoes of most of our first world retirement nest egg. Another would be time and human capacity lost through armed conflict brought on by AGW. Another would be loss of human capacity to implement change through the human depletion of climate and conflict refugees. I (try not to) watch Trump flail away at the best allies the US has in addressing AGW and think the political system of the US is really a disaster for the planet in the climate emergency.

Richard? You want to tax breathing or you oppose taxing breathing? I skim over your comments quickly because they contain so little real and/or useful content. You are trolling. You should get tossed off the discussion unless you start to bring something of value and substance to the discussion.

Cheers to the folks who engage critically, intelligently and in good faith and authenticity.

Mike

You are right, DG, the product liability question is complicated, but the proper analysis is a comparison of the fossil fuel industry to the tobacco industry, rather than a comparison of fossil fuel to water. But in any case, I think we agree, let’s not go there, it’s a waste of our breath. The adversarial litigation processes may be essential to address bad actors within a socio-political-industrial society, but they should be the last resort and should not take away from authentic, good faith efforts to be a good actor within such a system, and particularly within such a system that is in crisis (assuming that such systems are capable of existing outside a crisis state, a fact I hope, but am not certain, is true)

Mike

@smallbluemike,

In the theory of shared resources, there’s tragedy of the commons which most everyone is familiar with. Mark Carney (BoE Governor) has introduced the idea in addition of a tragedy of the horizons (see also), meaning that because this kind of thing is completely new and there are no measures relevant to accounting for reflecting future risk of climate change or regulation to mitigate or adapt to it, managers and investors are flying blind, only able to see out to the horizon their measures can reflect things, and not beyond. It’s kind of like insisting that climate damages and mitigations be based upon actually observed climate values now rather than well-substantiated projections, or historical trends rather than projections, except worse.

OT, but of interest –

Changes in Earth’s Energy Budget during and after the “Pause” in Global Warming: An Observational Perspective

Mike says:

“Richard? You want to tax breathing or you oppose taxing breathing? I skim over your comments quickly because they contain so little real and/or useful content. You are trolling. You should get tossed off the discussion unless you start to bring something of value and substance to the discussion.”

I think if you read my comment again (and don’t skim), you will figure it out.

I am not trolling – but pointing out that assessing damages to every human would be pointless. We all use energy after all and we all emit CO2.

I am pro-nuclear and think we should be generating (in the USA where I live) 60-80% of our electricity from nuclear, rather than the 20% we generate now. That is my preferred solution to CO2 emissions.

If you can get me banned from this discussion – go for it.

@Richard Arrett,

Yes, nuclear would make logical sense — if we knew how to build them.

“Yes, nuclear would make logical sense — if we knew how to build them.” Or if we knew how to clean up when the project goes wrong. Or if we how to store the nuclear waste that continues to accumulate.

Yes, I am also fine with nuclear as long as the proponents of that technology agree to take a couple hundred pounds of the nuclear waste to their homes and play around with any bright ideas they might have to solve the waste problem that accompanies the energy creation. Or, if you don’t want that project and don’t want to have the stuff on a shelf in your garage, just have the proponents agree to spend a couple of weekends every year at Hanford, Three Mile Island, Fukushima or Chernobyl reclaiming a little ground that has become a little toxic according to the nuclear regulatory agencies and the folks who tend to oppose new nuclear. Is it too much to ask that the proponents of nuclear energy put a little skin in the game by engaging in the cleanup of accident sites or the storage of a small amount of the nuclear waste that seems to be a storage problem?

I think nuclear is a good example of a technology that is a tragedy of the horizon, as well as a tragedy of the commons, but I could be wrong. I remember when I was a kid, nuclear energy was touted as the energy source of the future. I think this is an accurate quote from that era:

Lewis Strauss, Chairman of the US Atomic Energy Commission, while addressing the National Association of Science Writers, September 16, 1954: “Our children will enjoy in their homes electrical energy too cheap to meter,” he declared. “It is not too much to expect that our children will know of great periodic regional famines in the world only as matters of history, will travel effortlessly over the seas and under them and through the air with a minimum of danger and at great speeds, and will experience a lifespan far longer than ours, as disease yields and man comes to understand what causes him to age” (The New York Times, September 17, 1954)

Some of the pro-nuclear folks sure get excited about the prospects for that technology. I don’t know? Could they be wrong about the promise of nuclear energy?

Going camping for a week or ten days, so this my last thought about these questions for now.

Warm regards all,

Mike

I think it would be a mistake to not use the legal system to the greatest extent possible – that to assume those with fiduciary duties are beyond legal accountability without testing it in courts of law first would be premature. Probably more than once as the failure of one case does not mean others won’t have legitimate grounds. And different aspects may require different cases; the Netherlands example was against their government for endangering them by failing to have policy in keeping with the expert advice – not seeking damages for climate harms.

The potential for being held accountable in the future is probably already a consideration in decision making and given the paucity of avenues for action and the extreme stakes I would not give up on this potential tool for change.

I wonder why the Richies of ClimateBall do not cite this kind of tidbit:

Mike asks “Is it too much to ask that the proponents of nuclear energy put a little skin in the game by engaging in the cleanup of accident sites or the storage of a small amount of the nuclear waste that seems to be a storage problem?”

I would be willing to host some of the spent nuclear waste at my home (buried in the backyard). Especially if I could reprocess it in my own personal reactor, perhaps a small modular reactor. Maybe someday.

Would you be willing to take some of the dead birds killed by wind power into your home? Or listen to the weird noises from a wind turbine close to your home?

Would you be willing to clean up some of the mining damage caused by mining rare earth metals for solar panels or lithium for batteries for storing wind or solar power?

I think any fair comparison to Earth damage from nuclear versus wind or solar would be in favor of nuclear. Already stories are being published on the tremendous environmental costs for the large number of panels and the mining damage required for an all electric car future or many many more solar panels. They may dwarf the potential damage caused by nuclear power – especially if only safer fourth generation passive cooling reactors are built going forward. But that is just my opinion.

Have a great weekend.

> I would be willing to host some of the spent nuclear waste at my home (buried in the backyard).

Have you asked your neighbours, RickA?

Speaking of neighbours:

https://twitter.com/ThatEricAlper/status/1016396670190477315

@Richard Arrett,

Sure, there is some mining damage from solar, but that’s a startup cost. Also, compared to the pass given fossil fuel mining over the decades, not to mention that for Uranium or Vanadium, or coal, that’s completely negligible.

Facts are, the most efficient and economically productive solar manufacturers instituted a recycling and producer responsibility plan for their solar panels From Day One, for example, SunPower. Our panels, by contract, cannot be disposed of casually, but must be returned to Sunpower or their assigns when they achieve their lifetimes. Similarly, for Tesla, and other EV manufacturers, the owner of the auto doesn’t own the battery, they lease it. Why? Because it has a life beyond the EV, for a solar home, or as recycled material.

Just because you cannot imagine a business like Unilever or Virgin operating in this way does not mean it is impossible.

Show me a fossil fuel company or a nuclear company that takes the same attitude towards their waste products. I know: I worked for Westinghouse Nuclear Automation for a time, and their attitude was disgusting.

Nuclear power is selling a very large scale generator that works with a centralised hub distribution and is most efficient when run at high power continuously. It is not effective at small scale or in variable demand operation.

It requires stable, non-corrupt, and strong local government and oversight by a global authority.

While the shift in energy systems is towards resilient distributed networks of smaller scale intermittent generation that do not require the centralised authoritarian oversight that Nuclear demands.

It is the wrong shape and size of technology to meet current and future demand, and requires a form of authoritarian governance at local and global levels that is often unacheivable, or politically unstable.

It is like proposing building a very large out-of-town mega-store with massive car park to provide people with their food, just as the market is shifting towards home delivery from local farmers and specialised distributors.

Are those stories being published somewhere credible that tells the truth Richard, or only on places like Breitbart?

Richard,

Burying the waste just got safer

http://www.deepisolation.com/news-events/

of course you neighbors will have to agree with what the science shows

http://www.deepisolation.com/policy/

One thing is for sure, the current storage many neighbors put up with is less safe.

I don’t know if the US will push for more nuclear. But whether they do or not is immaterial to the task of safer storage than we have now.

cool willard.

nice game

https://github.com/abouchakra/Collective-Risk-Dilemma

next step is let humans play it like a board game.

The concern for dead birds is so touching. I feel the irrationality too, so I fantasize about killing all the cats. The Marine Corps would love the target practice. And banning glass. Fly, fly birdies.

A repeat of the comment I just posted on the thread to the Zero Emissions OP,

Here’s an insightful analysis of the bleak future of nuclear power by David Roberts.

Scientists assessed the options for growing nuclear power. They are grim. by David Roberts, Energy & Environment, Vox, July 11, 2018

Roberts’ article is based on the findings contained in

US nuclear power: The vanishing low-carbon wedge

M. Granger Morgan, Ahmed Abdulla, Michael J. Ford, and Michael Rath

PNAS July 2, 2018. 201804655; published ahead of print July 2, 2018.

https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1804655115

ya grim

“Our children will enjoy in their homes electrical energy too cheap to meter,” he declared. “It is not too much to expect that our children will know of great periodic regional famines in the world only as matters of history, will travel effortlessly over the seas and under them and through the air with a minimum of danger and at great speeds, and will experience a lifespan far longer than ours, as disease yields and man comes to understand what causes him to age” (The New York Times, September 17, 1954)

Which of the above came true? Which did not? Of those that did not, which failures were the result of political opposition, as opposed to degree of difficulty of the solution?

Just Asking Questions gets boring fast, Ted.

If you have a point, make it.

tedpress

@-“Which of the above came true?”

Air and Sea travel are far faster and safer than they were in 1954.

Famine, disease and aging are still with us.

The last two because of the degree of difficulty of the solution, The first also involves some political opposition.

izen, but famines are far less frequent than in 1954. So is disease. And longevity has increased dramatically.

Just a reminder, for those who need to pre-judge comments, this is Tom Fuller posting under a different user identity.

Acknowledging one’s sockpuppet is good.

Sticking to one’s ClimateBall identity is better.

Will climate change puts a kink in that nice correlation between passage of time and famine reduction? People with appropriate expertise are asking this question very seriously and coming to the conclusion that it will.

tedpress

@-“but famines are far less frequent than in 1954.”

Citation needed. After all there have been six famines with over a million deaths since 1954, and several drought caused famines in Africa with smaller death rates.

” So is disease. And longevity has increased dramatically.”

Infectious disease from contaminated water has been reduced, but I suspect it is offset by the obesity and diabetes epidemic. Fewer people may die early because all/many/some have access to healthcare. But wider availability of effective treatment does not imply less disease.

Longevity is the same as it was in 1954, there has been no breakthrough in biology on the cause of aging, or delaying it. Many more people share in the longevity enjoyed by the lucky few in the past because better sanitation and healthcare prevent a premature death. But the maximum has not changed significantly, just the proportion able to reach it.

Most of this improvement is the result of government prescribed collective welfare/healthcare systems in the developing world, with universal access according to need being a key component.

Famines

by Joe Hasell and Max Roser

First published in 2013; substantive revision December 7, 2017.

This entry focuses on the history of famine and famine mortality over time. Our data include information only up to 2016. This does not include any data on the current food emergencies affecting Yemen, South Sudan, Somalia, Nigeria and Ethiopia. More information on these crises can be found at FEWS.net.

A famine is an acute episode of extreme hunger that results in excess mortality due to starvation or hunger-induced diseases.1 It is this crisis characteristic that distinguishes it from persistent malnutrition, which we discuss in another entry on this website. As we discuss in the Data Quality and Definition section below, the term ‘famine’ can mean different things to different people and has evolved over time. It is only in recent years that more precise, measurable definitions – in terms of mortality rates, food consumption and physical signs of malnutrition – have been developed.

But despite these ambiguities, it is nonetheless very clear that in recent decades the presence of major life-taking famines has diminished significantly and abruptly as compared to earlier eras. This is not in anyway to underplay the very real risk facing the roughly 80 million people currently living in a state of crisis-level2 food insecurity and therefore requiring urgent action. Nevertheless, the parts of the world that continue to be at risk of famine represent a much more limited geographic area than in previous eras, and those famines that have occurred recently have typically been far less deadly – as we will go on to show in this entry.

https://ourworldindata.org/famines

Life expectancy, Africa: 1950 35.6, 2001 50.5

Americas: 1950 58.5, 2001 73.2

Asia: 1950 41.6, 2001 67.1

Europe: 1950 64.7, 2001 76.8

Former Soviet Union 1950 56.1 2001 66.6

Oceania 1950 63.4 2001 74.6

And yes, improvements and access to sanitation, clean water and healthcare account for almost all of it.

tedpress

@-“Life expectancy…”

I thought you might be confusing life expectancy with longevity.

The original quote talks of a “lifespan far longer than ours”

Suppose you make a smart-phone with a battery life of ~70,000 hrs. After which it wont recharge and the phone is dead.

That is okay because the phone is fragile and 90% have been dropped, got wet or had the electronics fried by static well before the lifespan of the battery is reached.

Then a cheap cover is supplied that protects it and many more survive in working condition up to the time the battery starts to fail.

The life expectancy of the phone has increased, but the longevity, the lifespan is the same.

I would concede an improvement in famine statistics.

WW1 and WW2 rather distort the pre-1950s figures and rating famine as deaths per the total global population obscures the fact the total number in the 60s/70s equalled the long term average.

But perhaps it is progress that although similar numbers are affected, intervention prevents as many deaths, and that is a smaller percentage of the increasing global total.

I provided answers to your questions in the forlorn hope (cynicism prevented expectation) of it eliciting the reason for the questions. But you have just quibbled with the answers.

Do you have a point to make related to the relative failure of the 1954 predictions that is at least somewhat related to the goal of zero emissions ?

If past predictions are any indication, it is that technological magic will not deliver us from disaster, and political opposition will perpetuate problems.

Your longevity error has already been pointed out ted. Should have recognised the style, Tom: “by his works shall ye know him”. Graph from the article:

So. Lots of biggies in the 19th century, Unclean water, no antibiotics, minimal healthcare, undeveloped international markets, no UN, so not relevant to more recent times. 20th century: wars and major political upheavals such as Stalin’s ethnic cleansing, Mao’s great Leap Forward and Year Zero. You didn’t cherry-pick the 1950s by any chance? Just askin’. I pick the 1980s as my baseline, when global warming rose above background variability. A nice, objective choice, not a cherry-pick.You were inferring something along the lines of global warming making famines scarcer because CO2 is plant food, weren’t you? Or was it something else equally silly?

Nice upward trend since the 1980s. Jury still out on this decade. “This does not include any data on the current food emergencies affecting Yemen, South Sudan, Somalia, Nigeria and Ethiopia”. And we have to see how the Syria end-game plays out.

You’re spending too much time in Denierville ted. Have you forgotten that here on Planet Rational, people click through links to determine whether or not they support the case you’re making or appear to be dog-whistling? In this case, as so often in the past, the answer is “not”.

I was thinking maybe I had been a little bit harsh there ted. But then I remembered I’d downloaded the data which is listed at the bottom of the page.

Hmm. 1960s 16 million. But the Great Leap Forward killed 24 million. Aha! They’ve apportioned it between the 1950s and 1960s. Look at the graph. The label spans two columns, unlike the other labels. 8 + 16 = 24. Hmm. Were there any other famines in the 1950s? Yes: Tigray, Ethiopia. 248,500. So excluding Mao’s Madness, the 1950s was a remarkably famine-light decade. Lower than any subsequent decade, and just lower than the current decade to 2016. So the 2010’s will be comfortably above the 1950s when the recent famines are added in. So unless your cryptic just-asking-questions comment was because you somehow think the Great Leap Forward is relevant to the blog topic of zero emissions, you’ve erred by including its numbers in the 1950s. If it annoys you that I sometimes misconstrue the point of your posts, you should try saying straight-out-loud what your point is and not leave it for the audience to guess.

Let’s exclude the Great Leap Forward and Year Zero. Hopefully we can all agree they were exceptional events not due to things like climate change, technological advance or the benign influences of UN agencies and charities.

1950s: 250k

1960s: 900k (or 150k if we exclude Biafra because an unknown proportion was due to siege warfare)

1970s: 1.5M

1980s: 1.4M

1990s: 1.3M (or 900k if we exclude the Congo war)

2000s: 1.5M (or 300k if we exclude the Congo war)

2010s: 250k by 2016

So on refelction I see no trend. Which is not surprising because just as AGW was happening before the 1980s but only emerged above the level of natural variation then, so extreme events have been increasing but only recently have started to rise above naturally variability. You’d expect that to be delayed, even if the signal is was strong or stronger, because the natural variability of individual, local events is much, much higher than that of global annual averages.

To go back to the question, the common theme other than war or political madness tends to be governments (often insular, totalitarian ones or failed or near-failed states) refusing to acknowledge it’s happening until it’s too late, and refusing outside help or delaying far too long before swallowing their pride.

[Playing the ref. -W]

It happens. Please don’t pay the ref.

Paying the ref is cheating/bribery. (sorry; couldn’t help myself &;>)

“Would you be willing to clean up some of the mining damage caused by mining rare earth metals for solar panels or lithium for batteries for storing wind or solar power?”

In 2017, the market share of all thin film technologies amounted to about 5% of the total annual production. https://www.ise.fraunhofer.de/content/dam/ise/de/documents/publications/studies/Photovoltaics-Report.pdf

The elements used in thin film solar cells – cadmium, gallium, indium, selenium, and tellurium – are all byproducts of copper, zinc, lead, and aluminum mining.

The other 95% are silicon, which are made from sand and coke(from coal or petroleum refining)

As far as the “damage caused by lithium mining” https://cleantechnica.com/2016/05/12/lithium-mining-vs-oil-sands-meme-thorough-response/ says it far better than I could

Speaking of oil sands, there’s probably enough petcoke (and sand) already on site – 57.080409, -111.660277 (latitude and longitude; plug into google maps)- to supply all the silicon necessary to make solar panels for the next 100 years.

@Brian Dodge,

Don’t know where you are coming to this issue, as, to me, it wasn’t clear from your comment, but to the question of environmental impact of solar, wind, and batteries to support, say, EVs:

(1) It is a moving the goalposts problem because the same consideration, in a critical sense, is not applied to these technologies competitors, namely, fossil fuels, including oil, coal, and natural gas.

(2) Any new technology, in its process of getting launched, will, almost by definition, demand a support for the launch pad which relies upon existing technologies and infrastructure. Once underway, they can cut free of that, both in terms of having recycled materials and, if they have profits, reinvesting them to find better sources.

(3) There is no incentive for these technologies to continue to rely upon rare earths and other marginal materials. To do so would limit their growth. So, for example, in the case of wind electrical generation, AFAIK all recent wind turbines use generators which do not rely upon rare earth magnets and, instead, depend upon wire coils to set up the magnetic fields. Similarly, it only makes sense to set up long term recovery and producer responsibility chains for these products. Our Sunpower panels cannot, in their end of life, be arbitrarily disposed as a condition of our purchase agreement. Sunpower is entitled to buy them back first, in order to use their materials in a closed recycling loop. Indeed, this is one of the main reasons we chose Sunpower as a panels provider.

(4) The environmental and social costs imposed by startup needs for new technologies can be returned by the environmental and social benefits earned when these new businesses destroy the fossil fuel-dependent competitors upon their success.

“1950s: 250k

1960s: 900k (or 150k if we exclude Biafra because an unknown proportion was due to siege warfare)

1970s: 1.5M

1980s: 1.4M

1990s: 1.3M (or 900k if we exclude the Congo war)

2000s: 1.5M (or 300k if we exclude the Congo war)

2010s: 250k by 2016

So on refelction I see no trend.”

This is interesting. DK and I were discussing what constitution misinformation when it came to making claims about trends and such.

I’ll await dk’s judgement

Famine trend, assuming no autocorrelation (so the with-Congo one is not strictly correct because the war spanned two decades):

With Congo: gradient = 35,000 per decade, R2 = 0.019

Without Congo: gradient = -11,000 per decade, R2 = 0.0015

Do you rally want me to do a t-test? Pretty sure it won’t pass any sensible threshold, but even if it does, the effect size is so small as to be meaningless.

I think you would still fail dk’s test.

Lets see what he says. Wasnt my test. It was his.

Summer is not the proper season for silly greenline tests, Mosh.

This does not bode well…

The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) said the rising temperatures were at odds with a global cyclical climate phenomena known as La Niña, which is usually associated with cooling.

“The first six months of the year have made it the hottest La Niña year to date on record,” said Clare Nullis of the WMO.

Heatwave sees record high temperatures around world this week by Jonathan Watts, Environment, Guardian, July 13, 2018

Not a greenline test if you followed the thread, but interesting that you would perceive it as such.

Pingback: 2018: A year in review | …and Then There's Physics