There’s an interesting new paper by Katharine Ricke and Ken Caldeira called Maximum warming occurs about one decade after a carbon dioxide emission. The basic result of the paper is that the median time between the emission of some CO2 and the maximum warming from that emission is 10.1 years (90% range from 6.6 – 30.7 years). This leads the authors to conclude that

Our results indicate that benefit from avoided climate damage from avoided CO2 emissions will be manifested within the lifetimes of people who acted to avoid that emission. While such avoidance could be expected to benefit future generations, there is potential for emissions avoidance to provide substantial benefit to current generations.

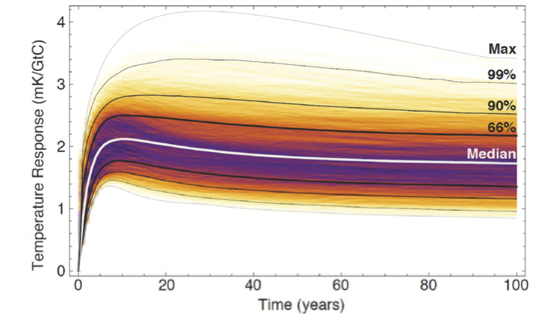

The main figure from the paper is below, and shows how the maximum warming occurs after about 10 years and that the warming is about 2oC per 1000GtC.

I must admit that it took me a little while to understand what was going on in this paper as I was surprised that the peak warming occurred so soon after the emission. In fact, the paper starts with

It is a widely held misconception that the main effects of a CO2 emission will not be felt for several decades…… Indeed, a co-author on this paper has previously said that ‘it takes several decades for the climate system to fully respond to reductions in emissions’2. Such misconceptions extend beyond the scientific community and have played roles in policy discussions. For example, former US Energy Secretary Steven Chu has been quoted as saying, ‘It may take 100 years to heat up this huge thermal mass so it reaches a uniform temperature …

Although, I think I now understand this paper, I think the comment above is possible a little unfair and a little unfortunate. I think what’s being shown in this paper is related to what I discussed in this post and what Steve Easterbrook discusses here. In the Ricke & Caldeira (2014) paper, I think they considered abrupt CO2 emissions but also included the carbon cycle in their models. Therefore, what I think is happening is that the abrupt emission causes a certain rise in atmospheric CO2. Subsequently, however, the atmospheric CO2 decays at a rate that essentially ensures that the resulting temperature rise will be closer to the transient response to the initial atmospheric CO2 concentration, than the equilibrium response to this initial CO2 concentration. Consequently, this also occurs quite quickly (about a decade, rather than many decades).

So, basically, what this paper is illustrating is that any particular emission will be responsible for warming to the transient temperature of the initial CO2 concentration that this emission produces, and that it will reach this temperature quickly. Therefore, this means that any reduction in emissions can have an effect on quite a short timescale, and also – presumably – means that any calculation of the social cost of carbon should take into account that emissions today can produce their maximal warming within a decade. However, I do think that there are a few things that one should bear in mind.

If we consider a particular instance in time, there will be a particular atmospheric CO2 concentration and the temperature will – at that instant – be the transient response to that CO2 concentration. Any emission will increase the atmospheric concentration and will, consequently, increase the warming to the transient response to the new atmospheric concentration. However, if we want to fix the temperature at that level, we cannot emit any more CO2 at all (i.e., we would need to reduce our emissions to zero). This seems incredibly drastic and highly unrealistic. Even if we want to fix the atmospheric CO2 concentrations at the current level, we’d need to reduce emissions by a factor of 2 almost instantly, another factor of 2 within 2-3 decades, and to a level one-tenth of the original rate within 100 years. Again, incredibly drastic and possibly also unrealistic.

So, even though what this paper is illustrating is probably correct (any particular emission will only be responsible for warming to the transient response to the CO2 concentration that this emission produces) I think we do have to be careful of thinking that the transient response is all that matters. At any instant in time, I suspect that it is virtually impossible to prevent us from continuing to warm to the equilibrium response to the current atmospheric CO2 concentration (and, given slow feedbacks, even beyond this). So, when we think of future warming, the equilibrium response and the thermal inertia of the climate system are relevant, even if each emission is only formally responsible for rapid warming to the transient response to the CO2 concentration it produces.

This post has got rather long a little convoluted. I also hope I’ve understood the Ricke & Caldeira (2014) paper properly. If anyone disagrees, feel free to let me know. I do think the result is interesting and what they conclude is reasonable; any emission reduction can have an impact on quite a short timescale and could, as they say, benefit those alive today, rather than only benefiting future generations. So, yes, any emission reduction has an impact, but the sooner we start reducing our emissions, the bigger the impact. We should, however, bear in mind that we can’t really reverse what we’ve already locked-in.

Mostly off-topic but not completely so (Anders, I’ll understand if you want to delete it – particularly since it is the first comment in the thread)….

But if anyone’s interested, I’d be curious to read responses to this article…and the concept of “hyperbolic discounting…”

https://www.sciencenews.org/article/discounting-future-cost-climate-change

Let me try to explain why people have difficulty with this (and this is tricky and I may not get this quite right). Transient climate sensitivity is a function of concentrations of GHGs (a stock) not emissions (a flow). The response to a fixed concentration of GHGs is a slow response—the “warming in the pipeline” we hear about—but the maximum response to a single slug happens sooner. A fixed concentration of CO2 in the air requires continuing emissions.

The main inertia in the temperature response is human (our inability to suddenly turn off emissions), not the physical response of the system, once you consider the carbon cycle. I tried to explain this here: http://www.skepticalscience.com/global-warming-not-reversible-but-stoppable.html

Of course, the other big environmental effect of a pulse of CO2, ocean acidification, does not peak after 10 years.

Andy,

Yes, that seems right.

That’s a great way of putting it.

Andy,

I think this point that you make in your SkS post, is essentially what I also took from the Ricke & Caldeira paper

Joshua,

I’m not quite sure what to make of the article about hyperbolic discounting. Maybe someone more knowledgeable than me will have some thoughts.

ATTP,

I think (so as i understand the Paper) the mainconclusion is true and if you look at Figure 1. and what happen after peak it looks realistic for me, because, after Doubling Co2 and if new Emssion=0 you get a short extrem warming (based on the short response to Co2) and a very very long Delay to get temperature like before (Because long-response to Co2 and the Delay-Time to decrease Emission species).

So in this Scenario, TCR would more help to get Max. Warmung and ECS is here more Usefull to make Delay-Time, because a larger spread between TCR/ECS would imply a stronger slow Respone. But in real World, there is a slow increase of Co2 and this imply, the climate has time to warm more to the slow responses.

Christian,

Yes, I agree, it think the main conclusion is true. I’m not sure I’m quite getting the rest of your comment. I think if emissions drop to zero, then you essentially warm quickly to the transient response of the CO2 concentration when emissions stopped. That is essentially what is shown in figure 1. Their median warming is just below 2K per 1000GtC. Emitting 1000GtC would increase atmospheric CO2 concentrations by 240ppm (say from 280ppm to 520ppm). This would produce a change in anthropogenic forcing of 3.3W/m^2 and hence 2K is closer to the transient response than the equilibrium response.

ATTP,

Andy shows in his Link what i try to say with my post. Its because of the slow responses to Co2, the climate will under apprupt Zero-Emission be very very long as warm as now. If you freeze Emissions, Temperature will increase as in Figure 1 on the Link of Andy on skeptical science.

Christian,

Okay, yes, I see what you mean. I agree.

Maybe I am oversimplifying, but if caught in a lift and needed to summarise, would it be right to say: the response to incremental increases in CO^2 is quick (10 yrs), but the time taken to wash out excess CO^2 from the atmosphere is long (at least 100 yrs) and so humans CAN help stop dangerous global warming in their lifetimes. But the footnote is this: if they fail to take action, there is no Plan B to get back to safe levels, because the inertia will have set in. Now is the best time to act. Later ‘nows’ are ok, but increasingly ineffective as we further procrastinate.

I could be wrong, but the paper looks to be another way of looking at things as described in the papers discussed at realclimate.org a few years ago. Maybe refined more (or not).

http://www.realclimate.org/index.php/archives/2010/03/climate-change-commitments/langswitch_lang/en/

I do recall reading elsewhere about the impact of a pulse of CO2, a fair while ago. It might have been one of the IPCC reports, or a paper. I can’t remember.

The full response is the CO2 impulse response (Green’s function) convolved with something that approximates the impulse response of the heat equation for thermal energy entering into the ocean. The CO2 impulse response is determined from the Bern model and the approximate heat equation impulse response is what Isaac Held recently derived (and I also derived ) that I described in a comment here a few weeks ago.

I tend to agree that the result will look like Figure 1. Both of the impulse responses are fat-tailed, so that the response will be very fat-tailed. It will also peak toward shorter times as Figure 1 shows.

Note that you use the word “convoluted”, but in not quite the right context 🙂

http://english.stackexchange.com/questions/64046/convolve-vs-convolute

Sou,

Thanks, I think it is the same basic idea. Zero future emissions essentially fixes the temperature at today’s value (or, possibly, a slight drop). Constant CO2 concentration would cause the temperature to rise to equilibrium but would require continued emission (an immediate drop of 60-70% according to the RealClimate post and then further drops after that to – I think – a level one-tenth of what they were before).

The final part of that RealClimate post is similar to what I was getting at here and similar to what Andy Skuce’s SkS post was pointing out

Nice that the maximum is after 10 years, but the response after 100 years is still very large (just looking at the figure). Thus I am not so sure whether the maximum is such a useful description of the time scale of influence of a CO2 pulse.

Victor,

Yes, that’s true for any actual emission. However, it does also illustrate that any reduction in emissions can have an effect even in the short-term. I think that is more the message that was being presented in the paper.

Doesn’t that depend on the type of emissions that are avoided? Avoiding dirty coal emissions, for example, might increase warming for a decade or two because of reduced sulphate aerosols.

Vinny,

Well, yes, and that’s discussed in Andy Skuce’s SkS post that he links to above. Clearly it’s not – in reality – quite as simple as this paper may indicate. However, I think the basic idea is about right.

In fact, I think the lowest emission pathway (RCP2.6) shows exactly what you suggests because it requires essentially halting all use of coal today, which results in a sudden reduction in anthropogenic aerosols and some warming in the short-term.

ATTP: ‘I think that is more the message that was being presented in the paper.’

‘Message’ is the word. It does seem to be science that has been polluted by the whole ‘framing’ thing.

Vinny,

Well, it’s clearly policy relevant, but I don’t have any issue with that. I think the whole “mustn’t say anything remotely policy related or we can never trust you again” is an attempt to get experts to not say things that might be inconvenient to those who would rather we ignored, than addressed, what is clearly a problem.

But doesn’t ‘framed’ hard science undermine the whole ‘the science says’, impartial authority, scientism thang?

Vinny,

I think that very much depends on what is being done. If there is a view that emission reduction today won’t have any impact for many decades and someone does some research that shows that in fact emission reduction today can have an impact within 10 years, how else are they meant to present it? All research is about answering/understanding something. It’s meant to be relevant, otherwise why do it?

What would be a problem is if scientists were concluding that we had to reduce our emissions and were stating how to do so. Pointing out the consequences of doing so – or not doing so – is, however, not specifically policy prescriptive, so I fail to see why it’s an issue.

I don’t know why VB thinks the word “message” is so nefarious. Pretty much any paper worth publishing has a “message” aka a “finding” or “point” or whatever you want to call it. The paper is intended to communicate something. That something is the message.

I guess I should express a certain admiration for VB’s dedication and tenacity in propagating … well, let’s just call it his “message”.

Little by little we are getting closer to reality. a) OLR is observed to rise with temperature. b) Now the models suggest that OLR recovers very quickly from a peturbation. See Donohoe et al, ’14:

” Observational constraints of radiative feedbacks—from satellite radiation and surface temperature data—suggest an OLR recovery timescale of decades or less, consistent with the majority of GCMs. ”

Closer and closer…

Lean & Rind (2009) use a lag of 120 months on the GHG-forcing. I have found an optimum of 122-123 months for longer series. Is that the same (weak) signal?

@-Vinny Burgoo

“But doesn’t ‘framed’ hard science undermine the whole ‘the science says’, impartial authority, scientism thang?”

No, compare with medical research, the hard science is in the chemistry, biology or physics of what was found. The cell response to a chemical or the climate response to a forcing.

The framing that you seem to object too is in highlighting the implications of that hard science finding to an important concern. The physiological response to a toxin or the climate response to a forcing.

An example, the Watson and Crick paper discussed the bonding structure of DNA – the hard science of the helix structure – and reserved the comment about the implications for inheritance to the conclusions.

So with climate response, the process is the hard science they are describinh, the implications for how human society controls its CO2 emissions are the important concern on which the hard science impinges.

Perhaps some people whould prefer it if science papers were all as magnificently understated in their conclusions as the Watson and Crick DNA paper !

so, this is one of those studies where CO2 emmissions are magically turned to zero after a point in time. Considering carbon trading the study would suggest then the early cuts in CO2 should be rewarded more than the later ones. I can’t see how this would be beneficial in getting the carbon emmissoins to a fixed level in a set amount of time, that is the goal (I think) of the international negotiations. Thus an absolute limit should also be needed. (Currently I’m thinking of a sea level of +15 to +25 meters above current, that could be acheieved rather simply I beleive by huge exchanges in agriculteural practises, changing to renewable sources of energy and one-child policy over most of the liveable land.) Not likely to happen. Perhaps I’m too pessimistic in my beliefs.

David Blake,

I have a feeling that you may misunderstand what’s going on here.

mrooijer,

I think it’s probably a similar physical process. In both cases I suspect it’s related to the time it takes for the well-mixed ocean layer to equilibrate with the land/atmosphere. I had heard values of less than 10 years for that, but 10 years is probably close enough.

jyyh,

Yes, I think that is right.

I think that is indeed what they’re trying to argue.

Yes, and this may get to the crux of the problem with a carbon tax. A carbon tax simply attempts to ensure that we pay now for the damages that our emissions with produce. This means, however, that we could choose to simply pay and take the damages. Therefore, a carbon tax may make the market more level (by internalising externalities) but it doesn’t really allow us to set any kind of target.

One way of looking at the results of that study is to reverse the direction of time and to use the curve to tell, how much releases at various past times affect the temperature at the moment being considered. The effects are not strictly linear, but close enough to make that approach meaningful.

Assuming that the median is closest to the truth, we see that emissions that occurred 10 years ago have the largest influence (are most efficient), and that emissions 100 years in the past have an efficiency roughly 80% of that maximum.

Can someone explain to me how the graph would look if it was made after our year by year emission instead of one single emission?

Thanks!

ohflow,

Technically the graph is the warming per GtC, so in a sense it doesn’t change. However, if you mean how would we warm if we continued to emit, rather than stopped completely, then it would look like one of the RCP warming graphs.

Izen: I agree that there’s nothing much wrong with including a few policy implications in a discussion at the end of a paper but this paper is presented as being policy-relevant from the start. It’s almost as though they went looking for something that would be be useful in pushing for reductions in CO2 emissions.

That said, the paper doesn’t seem quite as ‘framed’ as it did last night (perhaps because I’m not as ‘framed’ either). Unlike last night, I can now see that their results are interesting in themselves rather than only being interesting as potential policy weapons.

ohflow,

Actually, maybe the figure in this post is more what you were asking for.

Vinny,

Or, they were looking to do something that was both interesting and relevant.

ATTP said:

“ Yes, and this may get to the crux of the problem with a carbon tax. A carbon tax simply attempts to ensure that we pay now for the damages that our emissions with produce. This means, however, that we could choose to simply pay and take the damages. Therefore, a carbon tax may make the market more level (by internalising externalities) but it doesn’t really allow us to set any kind of target. “

Don’t you think that it would suffice if the level of a carbon tax for a given emission would reflect (at least) the costs of avoiding that emission? No need for lengthy discussions about what the damages exactly are and how they should be calculated.

IMO, the real/serious risk of severe damages merely justifies the introduction of a carbon tax on CO2-emissions. The level of the carbon tax however need not necessarily be coupled to these damages, as you seem to suggest.

Jac.

Vinny

If the electric soup is fuelling your paranoia and confusion, maybe you should dial it back a bit. And perhaps avoid commenting when “framed”.

Jac,

Don’t get me wrong, I’m in favour of a carbon tax. It’s possible I misunderstand it, but I have wondered about the moral issue. What happens if we decide to pay now for the future damages? Sure, we’ve internalised the externalities, but we haven’t actually prevented future generations from suffering as a consequence of our emissions.

In reality, though, what one might expect to happen is that if the carbon tax rises to correctly internalise the externalties, then alternatives become more and more viable and we would presumably then switch to the cheapest options which, eventually, would no longer be fossil fuel based.

It’s an invisible hand, gently propelling us in the right direction. But we have to create it first because the market has failed to do so and intervention is necessary.

@ATTP

Ah, I understand now.

You are probably right about the moral issue. Maybe paying now for future damages is morally justifiable, if the revenues of the carbon tax would actually be set aside and made available for the future generations to compensate them for the damages they suffer from our emissions.

Very unlikely to happen, though.

Saving for the future does not mean saving money, it means saving natural resources and environment as well as investing in things that will be valuable, including both material investments and knowledge.

The idea of sustainable development is that what we leave to the next generation is at least as valuable as what we got from the previous generation when all resources are taken into account. In that consideration the value of critical resources gets the more weight the more their availability is at risk (taking into account also potential substitutes).

@ Pekka

I am not sure I understand.

As ATTP pointed oud, putting a carbon tax on emissions does not in itself prevent the emissions and the damages they will/may cause, and therefor does not necessarily save natural resources and environment. Also, the revenues of a carbon tax need not necessarily be used for (investments in) combatting climate change.

What am I missing?

Jac.

jac,

I’m also not quite sure what Pekka is implying either. Also,

the preferred carbon tax is revenue neutral, so all that would happen is that we’d be moving the tax burden onto those who are emitting carbon. So, they’d be paying for their emissions, but the revenue would presumably be used to fund whatever was being funded before. So – as I understand it – it may incentivise a change in behaviour if there are viable alternatives, but doesn’t generate new tax revenues.

jac

Increasing the tax over time is supposed to incentivise decarbonisation at all levels, personal to macroeconomic. The revenue-neutral CT is supposed to fund the process, with accents on increasing personal and industrial energy efficiency and the share of renewables in the energy mix etc.

BBD,

I think that is what one would expect in practice. I do think, though, that if you speak with economists, they would mostly argue that it’s not about incentivising change. It’s purely about internalising externalities. You set the carbon tax purely on the basis of the cost of future damage. You’d expect it to incentivise a change if it became high enough to make alternatives economically viable. If it had little effect initially, then you’d certainly expect the carbon tax to rise to levels where this became likely. The concern I might have is that there is no fundamental target with a carbon tax. If someone finds a very cheap way to extract gas, oil, or coal, then the market may decide to continue to use fossil fuels despite the rising carbon tax.

What I mean is that carbon tax acts as incentive for changes in real behavior, but what’s collected as taxes doesn’t really mean anything on global scale, because more money does not mean more global wealth. Money represents a debt relationship. Summing the both parties of a debt gives a zero net result.

In many considerations it’s essentially to consider only real wealth, not money.

ATTP

I’m not convinced we can meaningfully separate the two. Internalising externalities causes a shift in market behaviour.

A good scientific article has a message: “A scholarly paper has to have something to say – it’s got to make a point – about something that the target journal readers will be interested in, something of some significance.“

BBD,

I agree. The point I’m trying to get at (maybe not all that well) is that in an ideal market-based scenario, if the carbon tax was set at the appropriate level and it was not incentivising change, then it would not be changed. So, the incentivising change is – in a sense – a side effect, rather than a goal. In reality, though, it would almost certainly incentivise change but (as I understand it) the level of carbon tax is not set with this in mind (ideally, at least).

In market economy the role of price is in a sense that of an incentive. Rising the price leads to reduced demand and increased supply. When the price is increased by a tax, the higher price applies to the buyer, while the price for the seller goes down. Thus the balance is reached at a lower volume that acts equally to both supply and demand.

Internalizing externalities is supposed to lead to the balance at the volume that’s optimal for the society taking also the external effects into account.

Can describe to me “skeptic” arguments they’ve seen against a “revenue neutral carbon tax” or as Bob Inglis calls it, “100 percent returnable emissions tax?”

Are the objections because the idea is unrealistic (too difficult to coordinate with other countries)? Are the objections merely because of ideological opposition to “government interference in the economy?” (which seems to me like it would be a zero sum scenario if emissions tax were balanced against income tax). Are the objections merely because of “unintended consequences” alarm about change to the status quo?

I read articles like this one:

http://www.vox.com/2014/11/11/7187057/global-warming-free-market-solution-republican-skepticism

And I’m struggling to understand what a “skeptic” opposition might look like, if not simply that they view win/win outcomes as a loss in terms of identity conflict. (Which, might also explain “realist” opposition to emissions taxes – if not arguments from “realists” that emissions taxes won’t be enough). Once someone is locked into an identity conflict about this kind of issue, anything other than a scorched earth victory would be seen as a loss.

Pekka,

Yes, I agree. I was simply making the point that it is simply a market-based approach and doesn’t, intrinsically, have the goal of reducing our emissions. I’m not against it and I’m sure it will have an effect. I also don’t really have any views as to alternatives, but I still think it’s worth bearing in mind that a carbon tax alone may be optimal in a market sense, but may not be optimal in the sense of minimising damages to future generations. Some might argue that the two are linked, but I’m not sure that that is necessarily the case.

aTTP,

I disagree.

The main purpose of the carbon tax is to reduce emissions. A secondary purpose is that it acts as a way of making those who produce more CO2 to compensate the damage that the others suffer.

Assuming that the carbon tax is set at the optimal level and that markets are efficient, all emissions are justified as producing more good than damage. Those who produce emissions receive the difference while those who emit little need not pay as high taxes as they would have otherwise. The overall well-being is at a higher level, because only those emissions are produced that have a positive net effect on the summed well-being.

Pekka,

This may well be the case. However, I’ve encountered those who argue it’s purely about price and not about reducing emissions specifically. I realise that this is slightly nuanced and so I’m not suggesting that we’re not intending to introduce a carbon tax so as to reduce emissions, simply that the goal is about price first. To be clear, I’m all for us introducing a carbon tax so as to reduce emissions. It is, however, my understanding that formally it’s about internalising externalities, not about reducing emissions specifically.

Yes, I agree. However, that’s a big assumption. So, yes, if this everything operates as it should, then the emissions will be justified as doing more good than damage. My view is simply that that is a big “if”.

Joshua –

It says ‘tax’ in it. That’s enough..

The real problem with a Carbon Tax is that whilst there is one large industry that is adamantly opposed to it (Coal), the effects are sufficiently diffuse that there is no specific champion. No one is going to get a big political ‘win’ out of driving through a Carbon tax but they will get a lot of pushback. And the US coal industry is big.

Well, I’m not sure what sceptic arguments are against revenue neutral carbon taxes as the optimum way to mitigate climate change, but there are some very powerful, overwhelming even, arguments against it being a sufficient vehicle, even if it could be implemented in a consistent global way with an international treaty. So I think I’m in a small minority in disagreeing that it’s the best way forward.

Here’s why:

1. The social cost of carbon is impossible to quantify meaningfully

2. A sudden rise in carbon tax to a level which fully recognises the social cost, howsoever calculated, would result in a massive economic shock.

3. If a slowly rising carbon tax is set, people will not act in a way which reflects its later increase; they will either be unaware or sceptical of later increases.

Taxation is not enough. Any effective mitigation strategy will need regulation as a large element of it. Smoking reduction is a good parallel.

All economic incentives are built on the assumption that markets are efficient enough to result in roughly the intended change in behavior.

Internalizing externalities can be used as a way of making the distribution of wealth more fair, but in all cases of internalizing the externalities related to environmental damage the main idea is surely to reduce the damage.

Pekka,

Yes, but I don’t think there is any real examples of an economy that works in only this way.

Why is the social cost of carbon impossible to meaningfully quantify?

The social cost is calculated from

– the impact of rising CO2 on the climate system. Note that sensitivity is only claimed by the IPCC within a factor of three, and the impact of rising temperature on sea level by perhaps a further factor of three!

-the cost of those impacts. In reality we have no idea on that. Let’s be generous and say we do know to within a factor of three.

-the discount rate applied to future costs and benefits. A change in assumption from just 2% to 3% in discount rate changes the cost of impacts in a century by a further factor of three

There you go. For sea level rise, we can accurately quantify the social cost of carbon to within a factor of 81. If we’re lucky

vtg,

Yes, you’re illustrating my issue with the idea that a carbon tax alone would be sufficient (I realise that “sufficient” is based on my own sense of what we should be aiming to achieve, not on some universally accepted goal of what we should be aiming to achieve).

ATTP

I have to say I, like Pekka, thought that the purpose of the tax was to incentivise decarbonisation. So the level of the tax (and rate of increase over time) are set to be effective for that purpose, not based on some estimate of future damage which has to be paid for with revenues raised.

This is a market-based approach in the sense that it provides an incentive based on cost and relies on the supposed rational self-interest of the players.

VTG,

What makes you think that regulation can be done in a way that leads to a better outcome than carbon tax, or even to think that a combination of both would lead to a better outcome than carbon tax alone?

Choosing the right level of government intervention is a problem, whatever the basic approach is.

One can perform a calculation for the net present value of taking action to prevent a certain asteroid strike exterminating humanity. If it’s more than a few decades hence, economically we’ll choose the certain destruction of everyone rather than expensive action now, even with a moderate discount rate.

Climate change is a moral issue.

Attempts to quantify climate change or its mitigation economically are useful in illustrating the moral issues involved, for instance, do we value poor people equally to the rich? However, whether we choose to take action or not, even if we were certain of the impacts, is a moral judgement, not an economic one.

In my humble opinion.

The full response is the CO2 impulse response (Green’s function) convolved with something that approximates the impulse response of the heat equation for thermal energy entering into the ocean. The CO2 impulse response is determined from the Bern model and the approximate heat equation impulse response is what Isaac Held recently derived (and I also derived ) that I described in a comment here a few weeks ago.

I tend to agree that the result will look like Figure 1. Both of the impulse responses are fat-tailed, so that the response will be very fat-tailed. It will also peak toward shorter times as Figure 1 shows.

> Choosing the right level of government intervention is a problem, whatever the basic approach is.

Whatever the topic is too. Goldilocks is tough to please.

However, this presumes that regulations imply government intervention. Wall Street is still ROFLing by the idea.

BBD,

Well, I thought it was the other way around. If you talk with people like Chris Hope, they say (IIRC) that the carbon tax is set on the basis of calculating the future damage due to emitting CO2, not on the basis of incentivising some change in behaviour. Yes, it will almost certainly incentivise a change in behaviour but as I understand it, the calculations are not done on that basis (i.e., the calculation is not based on achieving some level of emission reduction but is simply based on the cost of emitting CO2 today). If done properly, if it does not incentivisie change, then emissions will continue to rise, the damage calculation should result in higher and higher carbon taxes and, eventually, alternatives should become viable and take over from fossil fuels. However, I don’t think that the carbon tax calculation is associated, formally, with a specific level of emission reduction.

Pekka,

By no means a cmprehensive list, but there are areas where regulation is essential to any functioning market economy, Here are some which are particularly pertinent to climate change.

For some issues individual action is never the basis for decisionmaking now. So, for instance, we should regulate infrastructure investment to subsidise low carbon choices and penalise high carbon. More new cycleways, no new runways.

Some costs are not visible to consumers, These can be aided with visibility but also can usefully be regulated. Building standards regulations for thermal efficiency, for example.

Some issues have other externalities assocated. For example, obesity and climate change can be linked in that sedentary lifestyles are also carbon intensive. Encouraging public transport and walking combats both.

We do not allow motorists to pay more to speed more, we simply apply a speed limit. Inherently there is no reason we should allow people to pay more to emit more (although personally I think a carbon price of some sort would be a useful element of a mitigation policy).

ATTP

I can see that, but frankly the idea that the tax is meaningfully calculated from an estimate of future damages is risible, whatever the economists say. Worse still, It allows people to object to the quantification and stall the process, which is why VTG is correct to opine that regulation will be necessary. IMO, a tax is a regulation, but I assume he meant emissions curtailment by regulation, improved energy efficiency by regulation etc.

That an issue is an moral issue (whatever that means) does not tell, how it should be solved.

I agree that choosing the right level for the carbon tax is difficult, but it’s even more difficult to decide, what activities should be regulated and how. It’s easier to choose just one number than to define a full program that requires the government to make a correct judgement on many technical details.

There are at least two reasons for preferring a gradually rising carbon tax:

1) Sudden changes in the rules of economy cause transients that are damaging in unforeseeable ways.

2) The path need not be fixed fully far to the future. It’s essentially as effective to fix the later levels only as a range of possible tax levels and then choose the actual level based on what has been learned over the intervening time. The new knowledge may come from climate science, but I have principally in mind accumulating experience on the influence of the earlier taxation.

When the damages are local and affect some very strongly as the case is for traffic accidents and also for local environmental issues, regulation is an effective tool and the problems cannot be solved by getting all to behave properly on the average.

When the issue is truly global and when the only thing that really matters is the average behavior, then economic incentives like the carbon tax are likely to be far superior to regulation.

Pekka,

I disagree! Let’s take road speed as an example

In the UK, it’s regulated to drive beyond 30mph in an urban area and 60mph elsewhere.

How much do you think individuals should pay per mph to drive?

Which is easier?

Pekka,

we crossed. I’m glad we agree there are instances where regulation can be more effective.

So, let’s move on to

Shall we start with the Montral protocol, perhaps?

Or we could consider the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling ?

The case of the Montreal Protocol was relatively easy, because substitutes were available. The same result could have been reached equally well by both approaches. In whaling the number of actors is relatively small, which may make regulation clearly easier to implement.

I’m not actually convinced that the earlier claimed success of economic incentives in reducing sulfuric emissions in U.S. was a good case as the damage was too local for that. The outcome was quite good, but probably “for wrong reasons”, i.e. just because reducing the emissions turned out to be easy. Similar results had been reached in Europe through regulation.

CO2 emissions are, however, perhaps the best case for economic incentives and far from the best for regulation.

Pekka,

You imply a hard either/or on tax or regulate

Is that your view?

Until we agree with the Chinese government about the just right amount of interventionism, it will be impossible to do business with China.

VTG,

Some other measures do strengthen the influence of economic incentives. Such measures may have a significant role. They may mean regulation of the type that informs consumers on the economics taking the carbon tax into account in situations where it’s otherwise unlikely that they follow the economic rational. That means regulation of the procedures, not of the main activity that’s affected by the economic incentives.

Another set of measures that supplement economic incentives is formed from funding of R&D as well as demonstration and early deployment of technologies that are expected to become economic in the future, again taking the economic incentives into account.

Beyond this kind of measures I do think that a carbon tax would be the best approach assuming that it can be taken into account.

Unfortunately “tax” is a dirty word, and I have been told that even the Brussels bureaucrats abhor it.

winner

“That an issue is an moral issue (whatever that means) does not tell, how it should be solved.

I agree that choosing the right level for the carbon tax is difficult, but it’s even more difficult to decide, what activities should be regulated and how. It’s easier to choose just one number than to define a full program that requires the government to make a correct judgement on many technical details.”

yup.

Pekka knows how to get things done.

“The real problem with a Carbon Tax is that whilst there is one large industry that is adamantly opposed to it (Coal), the effects are sufficiently diffuse that there is no specific champion. No one is going to get a big political ‘win’ out of driving through a Carbon tax but they will get a lot of pushback. And the US coal industry is big.”

Not really.

I support this.

http://hardware.slashdot.org/story/14/03/12/1655214/environmentalists-propose-50-billion-buyout-of-coal-industry—to-shut-it-down

pretty simple get 50 million democrats who TRULY BELIEVE the planet is at stake to

donate 1000 dollars a piece and buy out coal.

jeez you guys must spend at least that amount on 420

> It’s easier to choose just one number than to define a full program that requires the government to make a correct judgement on many technical details.

Incentives imply regulation and government judgment calls, Pekka. The best you can argue is that the word “incentive” sells better than “tax” or “regulation.” From political philosophy, we now turn to marketing.

Pekka,

I think we might agree!

Perhaps an analogy is financial services, where strong regulation is essential both to ensure an overall outcome of economic stability but also to nudge consumers in the direction of their own long term well being?

VTG,

We may agree, but we should discuss proposals for actual implementation to know how closely we understand the concepts in the same way.

It may be better to avoid comparing with financial services as there if anywhere concepts get confusing. One of the peculiarities of financial sector is that it is dependent of regulation as provider of trust, but wants to minimize the limitations set by that regulation in its actual practice.

http://www.carbonfund.org

http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/climatechange/brief/world-bank-carbon-funds-facilities

http://sustainability.ucsc.edu/get-involved/funding/carbon-fund/about/index.html

Mosher

Collectively or individually?

What’s 420?

Mary Jane

But I did not inhale.

Oh, I see. No comment 🙂

I think it’s nice that old Steven M is so down with the kids.

Mosher:

A charitable interpretation is that he’s never heard of the free rider problem.

@ ATTP, BBD, Pekka, VTG

Is my understandig correct that in the ‘economist-approach’ as encountered by ATTP, a carbon tax is set at the level of future damages. And that the consequence thereof would be that we will accept any and all future damages just as long these are outweighed by the discounted costs of mitigation to prevent these damages?

My conclusion would be that this approach is a stricly economic approach that builds upon the a priori that maximizing ‘economic growth’ should be the one and only goal of a carbon tax and climate policy?

Also, perhaps as an illustration, it seems to me that in this economist-approach a the life of a person has little value and doesn’t count for much if that person does not produce substantical economic value.

In this approach I would expect that the life of a person living in the VS/Europe is worth more than the life of someone living in Africa/Asia, and hence that not mitigating to not hamper the economic growth of the VS/Europe is worth the lives of quite some Africans/Asians.

Please correct me if I am wrong.

Jac.

jac,

I think technically you calculate the future damages, apply a discount rate so as to determine the cost today and then apply that as a carbon tax. Therefore, technically, we pay for the future damage of anything we emit today. That, at least, is how I understand it.

I believe that it is possible to weight things so as to compensate for this, but I don’t really know how this is done. I have a vague memory of Tom Curtis and, maybe, Pekka discussing this at some point in the past, some maybe someone else can clarify.

“The whole aim of practical politics is to keep the populace alarmed (and hence clamorous to be led to safety) by menacing it with an endless series of hobgoblins, all of them imaginary.”

H. L. Mencken

Libertarians do not hold free riding as a problem, Mal. What you take as a bug is a feature that can be observed when they present themselves as conservatives.

Physics isn’t imaginary, Lucifer.

And that Mencken quote is worn paper-thin with over-use. Please strive for originality.

If Lucifer holds with Mencken why is he an economy alarmist and trying to distract from century old physics?

All serious attempts to calculate external costs value human life in some other way than solely based on the contribution of the individual to the economy. What the economic equivalent of a shortened lifespan or damage to health is, has, however, always been one of the most difficult problems in determining external costs. In many approaches it is true that the income level of the home country affects the result. That may be necessary to make the ratio of human life to other losses that occur in the same country similar across countries, but that may lead to problems at some other point of the analysis, when countries are included in the same analysis.

That’s not the only major difficulty of the approach but analyzing externalities gives useful information in spite of these problems. It may also give better guidance to decision makers that other deficient approaches – and all approaches have their deficiencies.

It’s also the rule rather than the exception that monetary values are summed up using utility functions that take into account that the same amount of money is much more valuable for a poor than for a rich.

In the stationary situation the goal is to make the Pigovian tax equal to the present value of the resulting external costs, in case of CO2 the carbon tax equal to the (discounted) present value of the damages from the release of CO2. That would align private interests with common interest, and lead thus to optimal behavior.

All this is idealized as the damages from various activities cannot be determined well even in physical terms and much less in monetary terms, but again we have the situation that no other approach is obviously better in helping to find objectively best policies.

I have in my bookshelf the book John Broome: Weighing Lives (Oxford University Press, 2004) that I bought based on advice of a Finnish economists. I read the book several years ago, and not very carefully, but the whole book is about the question of how to value human life in economic considerations and relative to other human lives.

John Broome is not an economist but White’s Professor of Moral Philosophy at the University of Oxford.

@ ATTP and Pekka

Thank you for your clarifications. It is very much appreciated.

Jac.

For numerous European countries, petroleum has had sky high taxes for decades.

Unfortunately, this has not led to practical alternatives.

But it does pose a conundrum to government.

Taxes do reduce consumption, but once the government starts receiving revenue from taxing something, it is faced with loss of revenue if that something actually diminishes to zero.

Of course, since the harms imagined are a fantasy, the whole thing becomes an exercise in funding the power hungry.

I just noticed that John Broome wrote a short book Counting the cost of Global Warming as early as in 1992. The full text can be downloaded from his page that I linked in my above comment.

The first paragraph of the conclusions of the 1992 book of Broome is as follows:

—

Global warming raises many difficult questions about our responsibility to the future. In this study, I have tried to bring some order the questions, rather than find answers to them. I have tried to map out the territory that needs to be explored, review the exploration that has already been done, and suggest some directions for future research. This chapter is a summary of my principal conclusions.

In Chapter 1, I outlined the present state of scientific opinion. The changes brought about by global warming are likely to be very large, and they will take place over a very long period of time. They are also very uncertain: the changes in climate are hard to predict, and the effects on human life much more so. These features put the problem of global warming beyond the normal experience of economics. We cannot expect the established methods of economics to handle them adequately. Conscquently, research cannot be limited simply to applying, say, the standard techniques of cost-benefit analysis to global warming. In this new context, for instance, we cannot rely on any of the conventional methods for fixing a discount rate. Fundamental theoretical work is needed first. This is not to say that action in response to global warming can be delayed. Governments need to act, but they must not think that their decisions can be made for them by straightforward techniques such as cost-benefit analysis.

—

I’m afraid that the reservations that Broome presents remain true in spite of all the work environmental economists have done. They have more sophisticated understanding of the problems, but I don’t believe that they have good answers.

The rest of the conclusions is worth reading, but you can download the book to read that.

I just wanna know, will the assessment of balance of harm include the harm of increasing flu deaths if humans actually would reduce temperatures?

http://www.businessinsider.com/r-cold-weather-can-actually-cause-colds-study-finds-2015-1

I think any global agreement will have to be flexible enough to allow each country to decide how they achieve the agreed upon emissions reductions. And a globally set carbon tax is not very flexible nor are global regulations that dictate what a country should do.

Joseph,

You refer to the agreed upon emission reductions. How do you think that they are agreed upon? Furthermore, how is that made flexible enough?

H. L. Mencken.

Yeah, let’s go with Mencken. Where can you go wrong if you think that people who enslave blacks are “superior,” and have that “certain noble spaciousness?”

H. L. Mencken

Yeah. Let’s go for that “aristocratic impulse. H. L. Mencken’s da man.

Thanks for the book, Pekka.

Would Ken please elaborate on why he objects to Steve Chu’s objecting that the hydrosphere’e thermal mass is three orders of magnitude than the atmosphere’s?

The half millennium turnover time of the oceans causes cogntive dissonance as well.

Well, to be fair to moshpit about 420 it is a California idiom (from San Rafael specifically) and he lives not far away. But using it still doesn’t make him hip to any degree.

For those who missed it, here’s the major feature of Jerry Brown’s fourth inaugural speech from earlier today:

So not enough, but a series of good steps outlined. Some of this will probably be done though an expansion of the existing cap-and-trade program, but there will be lots of regulation too.

In not-unrelated news, I notice that Tesla just announced they’ll be producing 500,000 vehicles annually by 2020, an order of magnitude greater than currently.

Speaking of Jerry, note also that California’s own 2013 climate consensus report (organized at his invitation by Tony Barnosky) is prominently featured on the right bar of his home page.

California is bigger than most countries and on this issue is acting like one.

Topical: Environmental Regulations Less Costly Than Opponents Claim, Says Study

Whodda thunk it.

An interesting development::

Hmm, something in the air?

“The full response is the CO2 impulse response (Green’s function) convolved with something that approximates the impulse response of the heat equation for thermal energy entering into the ocean. ”

I agree with WebHubbleTelescope. The “30 year response time” seems to arise out of this interaction and therefore I don’t think it’s a misconception. Although the paper says it addresses ocean inertia, it uses simple heat transfer models instead of thermal dynamics due to current oscillations. If the “hiatus” has taught us anything, it’s that the IPO is still a dominant player in global temps.

In fact, cryosphere and other slow term feedbacks certainly will override transient response, depending on when CO2 concentration stops; which was nicely highlighted in the post. Therefore, the framing of the paper intro is unfortunate.

In addition, it says “(Note that after one century, temperatures are still increasing in 119 of the 6000 simulated time series (i.e., have not reached ΔTmax) and therefore, if the simulation datasets available and analysis were extended for a longer time period, 2% of simulations would have fractional values greater than one.) In addition, even if the globally averaged maximum effect of an emission may be manifested after one decade, the results may vary spatially. For example, continued polar amplification may result in later a maximum warming effect at high latitudes.” which is a big deal when talking about feedback effects.

Therefore, while papers like these are nice to see for their narrow investigation, the presentation of an expected value is troubling from a risk context. I hate to see what someone like Tol could do with this paper, and the authors should be careful for what they wish for when presenting the wink toward discounting in the conclusion. After all, one could easily argue that rapid maximum response logically means that we can continue to delay action until we have verifiable proof that we’re close to catastrophic change and then immediately stop if we have to.

Mikkel,

Yes, that’s a good way of putting it. The paper was trying to highlight – I think – that what we can now can have an effect soon. However, it could be interpreted as suggesting that at any time what we do can have a rapid effect. The problem is that – at best – drastic action can prevent things from getting worse, but there’s we can do to reverse what we’ve already done. Additionally, slow feebacks (which this work doesn’t consider) will almost certainly act to amplify the warming.

Lucifer –

High petrol taxes in Europe have lead to the development of both highly efficient petrol engines and practical diesel cars (In my case, 48mpg and 0-60 in 9 seconds..); per-capita usage of oil is much less in the EU.

Problem is, if a car does 100,000 miles over 10 years at 40 mpg, that’s roughly 2500 gallons or £15k in fuel on a £20k car (plus perhaps the same in VED tax, insurance and servicing). So even with apparently extreme fuel taxes, fuel is only perhaps a third of the total transport cost, and the incentive to choose a more fuel efficient model is lower than you’d think.

This also applies to power generation. I would not like to think of the size of carbon tax required to make power companies go out and build zero carbon baseload plants as replacements for existing fossil fueled plant that is not End-Of-Life..

So.. a Carbon tax is useful, it means that people will tend to choose more efficient technology for new purchases, but it’s very hard to see how it gets us to complete decarbonisation on the timescales required.

@ Mikkel

“If the “hiatus” has taught us anything, it’s that the IPO is still a dominant player in global temps. ”

I would disagree. The PDO (scaled in the image) has very similar trends to the IPO. Would you say that this…

http://www.woodfortrees.org/graph/hadsst2nh/mean:30/plot/hadsst3sh/mean:30/plot/jisao-pdo/mean:30/scale:0.2

… is more closely aligned than this…?

http://www.woodfortrees.org/plot/esrl-amo/mean:30/plot/hadsst2nh/mean:30/plot/hadsst3sh/mean:30/plot/esrl-amo/trend

Clearly the AMO is more closely aligned. The correlation with PDO/IPO is poor. Which is obviously strange: the pacific is larger, the PDO range is higher, yet it’s the Atlantic that is more closely correlated with temperatures.

“After all, one could easily argue that rapid maximum response logically means that we can continue to delay action until we have verifiable proof that we’re close to catastrophic change and then immediately stop if we have to.”

The problem is that we can’t/won’t immediately stop, even if we have to.

David…very interesting. I remember reading a few announcements about a paper that stated so, but it hadn’t displayed the extreme correlation you just presented. At least 95% of the work I’ve seen focuses on PDO/IPO.

In my original comment I was tempted to write “closely aligned to decadal oscillations” without specifying, but the name dropping got the better of me. In any case, I’d say it supports my original contention about time scales in which we see climate response.

Correlation isn’t causation so any comments connecting Global Temperatures and Local, albeit large in are, Decadal Oscillations should be taken cautiously, if not outright proven false. I have no trouble of believing AMO & PDO/IPO and was there some SH decadal oscillation too have a noticeable local effect but since even the largest contributor to variation in the global temperature, the ENSO, is difficult to prove to have an effect f.e. in at least northern Europe (AMO messing with the effects) claiming these as somehow being drivers of global climate sounds really doubful and to convince me of the power of these just by statistics isn’t likely. That’s not to say some scenario in which these combine with a general warming/cooling trend to produce a jump to a hyperthermal (google Julie Brigham Grette) or hypothermal (abrupt cool episodes like Younger Dryas) locally, isn’t possible (like droughts during Maya collapse) Whether these would expand to encompass whole world and set in motion a change of the goelogical age would require other reasons too. They’re (by definition) Oscillations and would thus be neutral in their effect. As for the reason why earth could have these kind of multidecadal cycles I don’t have a proper answer, though likely this is oceanic in nature, as the atmospheric changes are way too fast. Could even be biological in origin. Maybe it just takes 30 years to change the temperature in the upper layers of the ocean so much there’s a system-wide ecological response. But that sounds all too much like Gaia theory so scrap that. Anyway these look like existing so changes in the heat transport (also other changes) between upper and deeper ocean would be seen at least somewhere.

It has a significant effect and is compositional to the global temperature signal. Remove the ENSO signal contribution and the global temperature clearly smoothens out.

[Response: This study includes carbon cycle modelling and is thus estimating sensitivity to emissions of CO2. In contrast, TCR and ECS are sensitivity to changes in concentrations. There is no contradiction here because the concentrations in the new study start high and then decline, compared to TCR (1%/yr increasing concentration) or ECS (permanent 2xCO2 concentration). – gavin] – See more at: http://www.realclimate.org/index.php/archives/2014/12/unforced-variations-dec-2014/comment-page-5/#sthash.YWjEEIn5.dpuf

JCH,

Thanks, that sounds about the same as what I suggested here.

Pingback: A bit more about committed warming | …and Then There's Physics

Pingback: The two-degree delusion? | …and Then There's Physics

It’s interesting to revisit this post after nearly six years and see how understanding and attitudes to feasibility and policy have changed. I’ve come back to read the post, but not all the discussion, because of a Twitter discussion on what the ‘policy-relevant’ ‘lags’ are in the climate system.

I’d agree with Ricke & Caldeira’s conclusion that ‘The primary time lag limiting efforts to diminish future climate change may be the time scales associated with political consensus and with energy system transitions, and not time lags in the physical climate system’, although the necessary infrastructure transitions identified by the IPCC extend to cement and other materials, land use and social change which also may have associated lags.

So one way to think of the global situation is that the climate response to emissions now happens now, but lasts indefinitely into the future. In that way it can be thought of as similar to biological extinctions. However, because of its long tail, it’s not conceptually like seeing _all_ of the damage within the lifetime of the actors (legally it’s not a ‘tort’, or rightable wrong?). This is apparent from David Archer et al, ‘The ultimate cost of carbon’ (2020), which looks at damages up to a million years in the future, building on his earlier ‘Fate of fossil fuel CO2 in geologic time ‘ (2005). Also ocean acidification and sea-level rise do not become fully apparent for an order of magnitude longer. And the thermal lag will show a gradual warming of oceans even if global mean surface temperatures remain constant, which may have consequences for marine life.

Sou mentioned Matthews & Weaver, which shows roughly flat temperatures if we suddenly go to zero, because the re-partition of CO₂ happens on about the same timescale as climate response, and you’re effectively integrating the effects of all the carbon pulses in the past up to the present moment. IPCC SR15 fig 1.5, published since, shows a similar flat curve, although slightly sloping upwards, provided ‘constant non-CO₂ forcing’. If aerosols are maintained but we stop emitting methane, nitrogen oxides, and F-gases we actually see a fall of (judging by eye off the graph) -0.4 °C (-0.8, -0.2). If aerosol emissions stop with the burning of fossil fuels but other greenhouse gases are held constant (which would require methane to continue to be emitted), there’s considerable uncertainty because the size of the aerosol effect is still unknown, but temperatures could rise 0.5 °C over a few decades (aerosol unmasking).

So response to constant emissions is ever-increasing temperatures until something breaks; response to constant concentrations, which this blog described as ‘incredibly drastic’ emission reductions over decades, but which is frequently modelled for theoretical reasons, is that temperature warms kind of asymptotically with about half of it occurring within the first twenty years; and the response to constant cumulative emissions (an ’emergency stop’ of emissions) would be roughly flat assuming aerosols and methane are also reduced, with a small short-term rise from unmasking, then a decline from reduced methane.

In arguing that ‘equilibrium response and the thermal inertia of the climate system are relevant’, this blog emphasised the second scenario, constant concentrations. That may be a future outcome, but I think it’s likely to be more complicated, one way or another. To argue for that, the antepenultimate paragraph now seems quite dated: ‘if we want to fix the temperature at that level, we cannot emit any more CO2 at all (i.e., we would need to reduce our emissions to zero). This seems incredibly drastic and highly unrealistic’. Within a year, 195 countries had committed to reaching ‘net’ zero emissions (a balance of sources and sinks) in the second half of the twentieth century. Finland has set 2035 as when its emissions will end, and the UK Committee on Climate Change (confusingly now, aka Climate Change Committee) explained it would be no more expensive than a 80% cut seemed in 2008.

How much of this change of thinking is drastic and how much realistic? It’s certainly not all down to Negative Emission Technologies, and the UKFIRES Absolute Zero report envisages a future with neither positive nor negative emissions, which does indeed seem ‘drastic’ but liveable. Running a system completely on renewables (possibly with some nuclear) through EVs, efficiency and heat pumps, industrial processes responding to cheap electricity now seems feasible and necessary. I’m really hoping it will still in another six years.

Pingback: Halting the vast release of methane is critical | …and Then There's Physics

Pingback: CO2 emission reductions | …and Then There's Physics

Pingback: A methane emergency? | …and Then There's Physics

Pingback: +2 °C – L'archivio di Oca Sapiens